Janet Martinez looks back at a time from her childhood within the Zoogochense community in Los Angeles. From this, she ilustrates the importance of creating visibility of migrant indigenous communities in the US through data and lived experiences.

Janet Martinez looks back at a time from her childhood within the Zoogochense community in Los Angeles. From this, she ilustrates the importance of creating visibility of migrant indigenous communities in the US through data and lived experiences.

Texto de Janet Martinez 06/04/22

Janet Martinez looks back at a time from her childhood within the Zoogochense community in Los Angeles. From this, she ilustrates the importance of creating visibility of migrant indigenous communities in the US through data and lived experiences.

“Instead of a map about indigenous death, we have a map about Indigenous life.”

— Mariah Tso, Dine cartographer

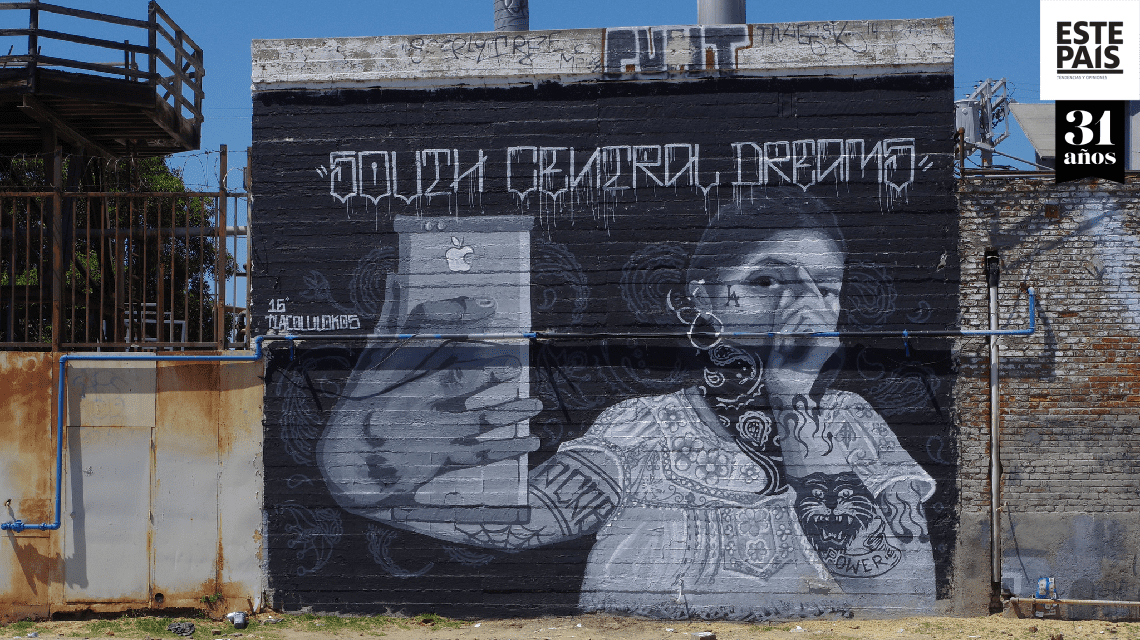

The music of the brasswind bands drifted in the night air. Filling our neighborhood streets in South Central Los Angeles on the last days of summer. The sound of the sones of the Zota hung in the air and it immediately reminded me of the summers spent practicing the dance. The Zota was organized when my grandfather was the president of the Hometown Association of La Unión Social de Zoogochense in 1999. At 10 years old, I could hardly understand the significance of the dances and the organization it took to put them together.

The Union Social Zoogochense was founded in 1967 by the first migrants from Zoogocho, whom establish a new home in Los Angeles. First came the men, then the women, and lastly their kids. During the summer of 1999, my grandfather was elected to serve as the president of La Unión Social. To be elected president is the final and last time you serve on the community leadership board. I imagine that’s what makes it more special. It is the opportunity to leave a mark, to leave a story that will be told over and over once you’re no longer here with the people that matter, your community.

My grandfather Everardo, fondly nicknamed el Pato, is funny and doesn’t mince his words. One of his favorite sayings is “la verda no peca pero incomoda”, which to this day he embodies. During that summer as president, he decided that he and his friend, Chucho, would hold the first danza performed by the children of the Zoogocho community, including myself, called la Zota, a danza that had never been danced in Los Angeles before. This meant that there was no one to teach us. The recreation of la Zota was built together with bits and pieces by our different dance teachers: Chucho, Lino and Esperanza. They searched their memory of when they performed it as children in Zoogocho. They would constantly ask each other, “How was that step?” Esperanza would dance it as Chucho would consult his memory. If there were no consensus, they would weave it together by watching old VHS of previous performances or searching for YouTube videos, looking for the missing piece of the danza. Once they agreed, Lino would whistle the music and perform the steps, and we would all then mimic him, wearing our huaraches in thick white socks in LA’s summer heat. The huarache pointed down like a pirouette and, point, point foot out in a line a motion; we would repeat this process over and over for months on Saturday and Sundays.

“…he and his friend, Chucho, would hold the first danza performed by the children of the Zoogocho community, including myself, called la Zota, a danza that had never been danced in Los Angeles before.”.

For lunch, our bellies would be filled by all the Zoogochenses whom donated food and drinks through the Union scheduled dates. There was a very long donation waitlist given that it was the first-time that children from the Zoogochense community would dance. Some danced to fulfill family promises to San Bartolomé, our patron saint; some others to honor him at his party. Therefore, there was a waitlist to feed the families and dancers. One Saturday was Julia’s turn. She brought mole, and capri suns and pizza for the kids. On Sunday, Eulogia made barbacoa and sandwiches and sodas for the kids. They would always bring two types of food, traditional food for the parents, and junk food for the children performing. If kids gravitated towards the traditional foods, there would be small compliments shared with the parents, “Oh, tu hijo come como en el pueblo.” They would gasp in awe while a proud parent watched on. These meals were able to happen because of every individual’s commitment to the community’s collective well-being. The union functioned as the thread that tied everyone together. They spent additional hours coordinating food, opening their homes to the dancers and their families. They would meet after they had worked forty-hour shifts in the restaurant to set up and put-up tables, chairs, and would spend hours on the phone coordinating who would bring the food what week.

When it was time to hire the band for the danza, Pato and Chucho went with their beers, water, and soda boxes to ask the banda de Yahuche band, a brass and wind band of a neighboring town to play for the Zoogochos, Zota performance. Lamberto, the band leader, happily agreed to learn the music that Pato and Chucho had gotten from back home. We practiced multiple times with them, and it was special. My grandmother Eulogia would cook her most famous dish, barbacoa, for when we practiced with the band. Out of respect to them and their solidarity, they would eat first and constantly take water, beers, and sodas. It was important to acknowledge their solidarity and unity that can be traced back into Sierra Norte of Oaxaca. As Bene Xhons we not only recreate music, we recreate steps to our dances, but most importantly we recreate community.

“We are resisting against the homogenizing label of “Latinx” that does not lend itself to the diversity of Indigenous migrant experience Angeles and our linguistic diversity.”

I share a glimpse of my experience to illustrate one lived experience that is shared by many Bene Xhons in Los Angeles. I understood my lived experience, but lacked the data to articulate it. How do you show with data, scientific proof that as Bene Xhon we exist when were constantly face statistical genocide in the census and official data that the nation-states generate? In response to this quandary as co-founder and vice executive director at Comunidades Indígenas en Liderazgo (CIELO), we started collecting data of the diverse Indigenous communities in Los Angeles. With the data collected we were able to create the first mapping of Indigenous communities in collaboration with Mariah Tso. We collected 2,500 unique data points in the city of Los Angeles. It is the first of its kind map that has the largest sample size of Indigenous migrant communities. We are resisting against the homogenizing label of “Latinx” that does not lend itself to the diversity of Indigenous migrant experience Angeles and our linguistic diversity. There are many organizations like the Unión Social Zoogochense that recreate community. There are approximately 42 Bene Xhon brasswind bands in Los Angeles alone, like the Yahuche banda leaded by Lamberto. Through this map, we are affirming our existence, resistance, and creating visibility of the Indigenous migrant communities. We are mapping the life we lead and the traditions we carry so far from home. EP