She puts her cell phone on the table and asks:

Which do you think is the real one?

Her question echoes through the hubbub of the cafe where we’ve been sitting for a while. What am I supposed to find when someone asks me to see the real? I hold the iPhone with my left hand and try to answer as soon as possible. The roles have been reversed: I have ceased to be the one who asks to be examined. I slide my finger over the screen, moving between images that look totally identical: a redheaded person on a bed surrounded by white sheets, next to a window bathed in natural light.

There is something mysterious in all of them. The only thing that tells me that there is a person in these photos, a real human being, is the bright orange hair. There are no features or faces, only wrinkled sheets as a result of the gravity with which the mass of the bodies is attracted to other masses, to other bodies.

I don’t know, I tell her, what about this one?. But no matter how hard I try, I can’t get it right. Then she smiles defiantly: this is it, look, as she takes the cell phone from my hands pointing a photo.

Zoila has asked an AI to generate images from a handful of words: young woman, red hair, waking up, window, bed, white sheets, New York. Artificial intelligence has created nine. Then, from them, Zoila has made the real photo, which is now confused among the others, blurring the line between the artificial and what we consider the law of all immutable laws.

***

From Ingeniero Maschwitz, on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Zoila remembers listening to the sound of birds next to her father. She was born in the nineties and grew up in the two thousand, which makes her recognize herself as half millennial, half centennial, and when she tells me that she always dreamed of a fabulous life, she doesn’t do it with the frivolity of someone who imagines that, a fabulous life, but with the simplicity of the girl who together with her older sister, secretly stole the clothes that her grandmother made for local theater companies to play at doing acts that she remembers to this day as her first glimpses of that deep interest in art and performance.

I don’t know what surprises us so much about Artificial Intelligence, she tells me, as she smiles at a girl who, from the next table, looks stunned as her auburn hair gleams in the mid-afternoon sun. For years we have given him absolutely all our information, like, do you remember? Those tests we did to find out which Disney character we were? Rather, with the AI I feel expectant.

Perhaps there is an advantage in not being afraid of changes, in glimpsing, like Zoila, the cyclical condition of things. And that lack of resistance to the unknown is perhaps the main starting point in her daily work. Long before Artificial Intelligence became the talk of the moment, Zoila was already experimenting with altering her selfies with retouching apps, seeing how the algorithms read her reality, her gestures and her world.

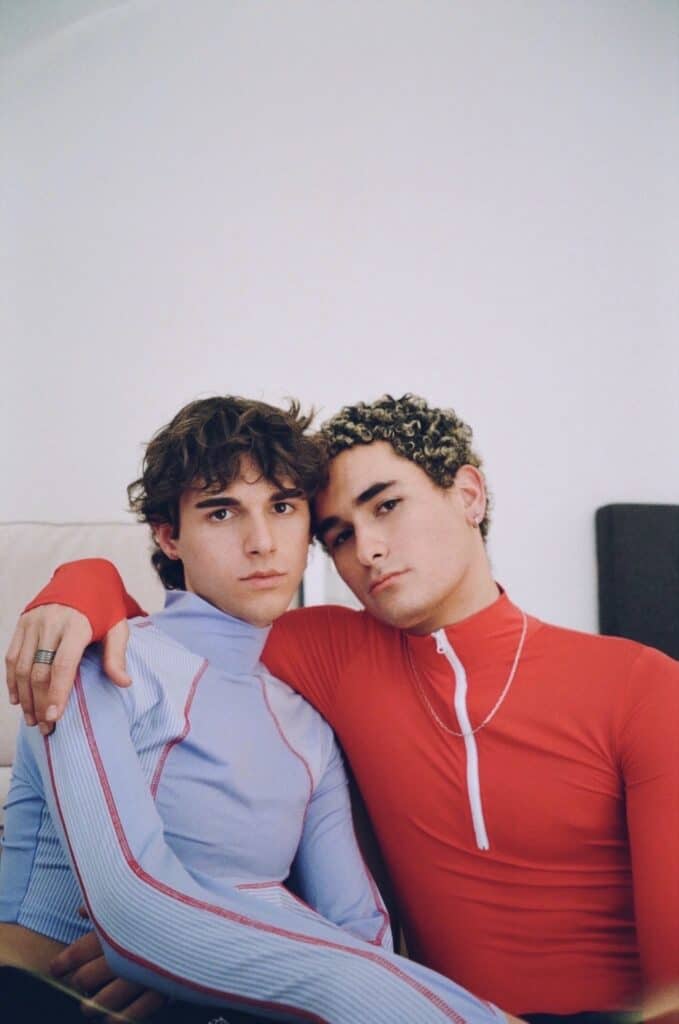

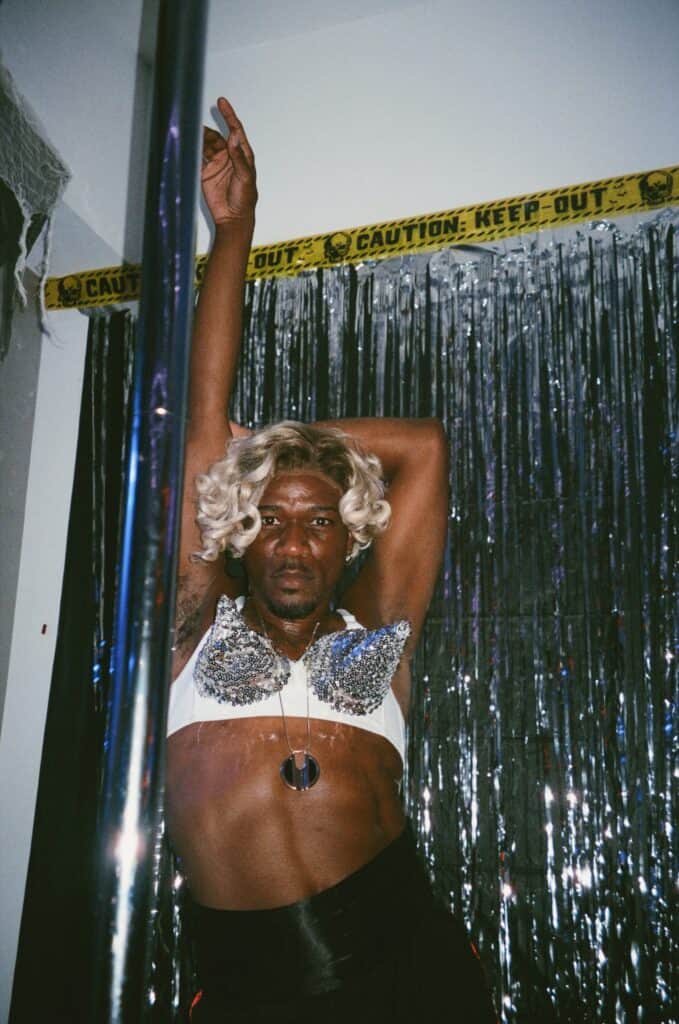

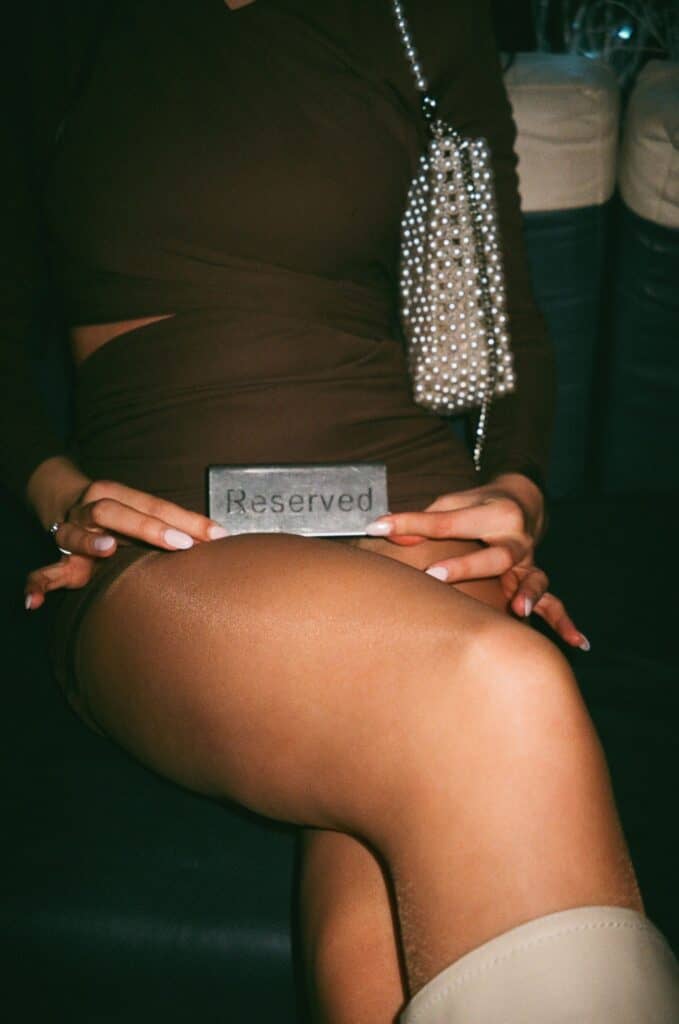

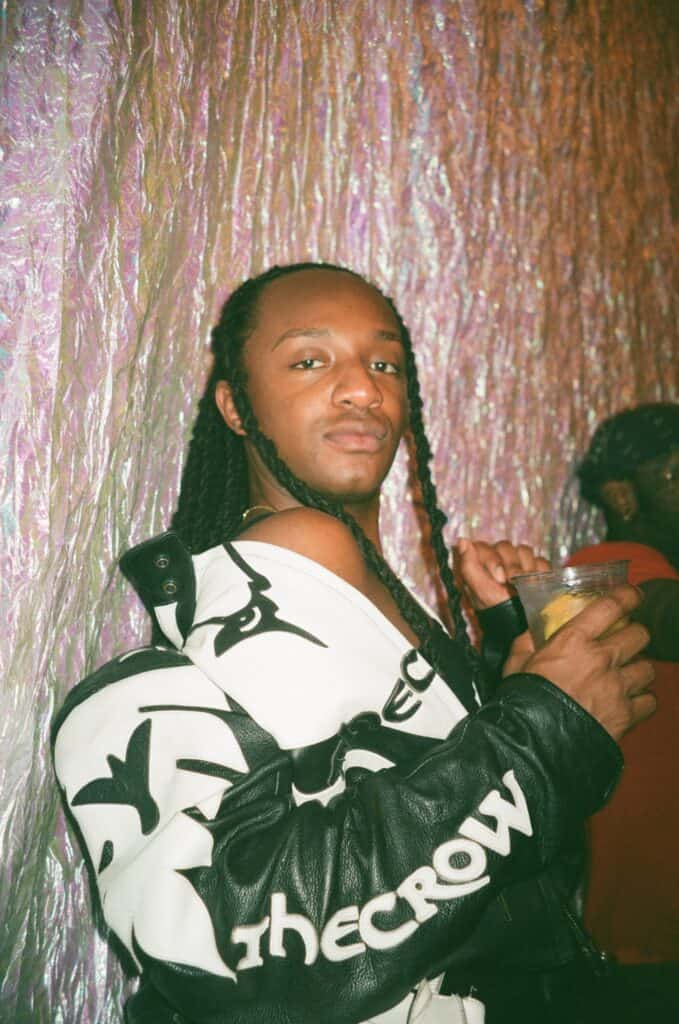

There’s something political about taking selfies, she tells me, as she pulls on black leather gloves. Her first camera was given to her by her uncle, and she describes to me in detail the afternoon they walked into a Best Buy in Florida to buy it as one of those moments that defined her life. Since that day she cannot understand her world without a camera. Whether with a digital camera, with a cell phone or with her 35mm point-and-shoot, Zoila translates the conventional day-by-day into images that tell her time, scenes of New York nightlife at massive post-pandemic parties, as well as fabricated juxtapositions, mini-fictions that say more about us, inhabitants of this voracious and uncertain city, than any other document that claims to do so from the accuracy of science.

We walked out the cafe door into a dying afternoon. The Brooklyn Bridge, a few feet from us over the East River, has turned gold. So we talked about conventions and how breaking with them does not mean absolutely rejecting what we understand as classic: hating the new, just because it is new, is for bluffers.

***

Sunday.

A group of friends have spent the afternoon at María Hernández Park, in Bushwick, and now we are walking down Irving Avenue, looking for decent avocados to take home. Suddenly, Zoila walks away from us to go talk to a stranger. The man, who is speaking on his cell phone, is dressed in pink from head to toe. Zoila stands in front of him with a camera in her hands and says only two or three words. The man smiles and nods. He takes a few steps and stops just where Zoila asks him to, in front of a garbage can.

The moment that passes between when Zoila talks to the stranger until she takes the photo, lasts the same as the time it takes for the traffic light to turn green.

Zoila is looking for juxtapositions, contradictions between her past and this afternoon walk through the streets of Brooklyn; she looks at objects, the materials they are made of, and forms seemingly unconnected scenes, first in her head and then through the lens, as when she inserts a handful of words into an AI and then the images are then returned to her screen.

Later, with a bag full of Michoacan avocados under the table, we eat cheese pizza at Roberta’s and talk, I don’t know why, about cherry blossoms. Zoila talks about them at length, in the same way, that she will tell me about her childhood in Argentina a few weeks later in a cafe next to the Brooklyn Bridge.

Sakuras bloom quickly and are short-lived, they are momentary, but that is what makes them fabulous. EP