On her desk, there is a boat. And a thousand other things. But the boat rests on top of everything, half-built, as if it had run aground on an island made of the ephemeral remains of someone’s life, and receives the last sun rays of the afternoon. So does a model car, a plane without wings, a smaller boat, a cutter, white glue, paintbrushes, a drill. And while I contemplate those involuntary archipelagos, I hear Victoria’s voice coming from the living room.

Her voice is soft and it is even softer when she is directing her subjects.

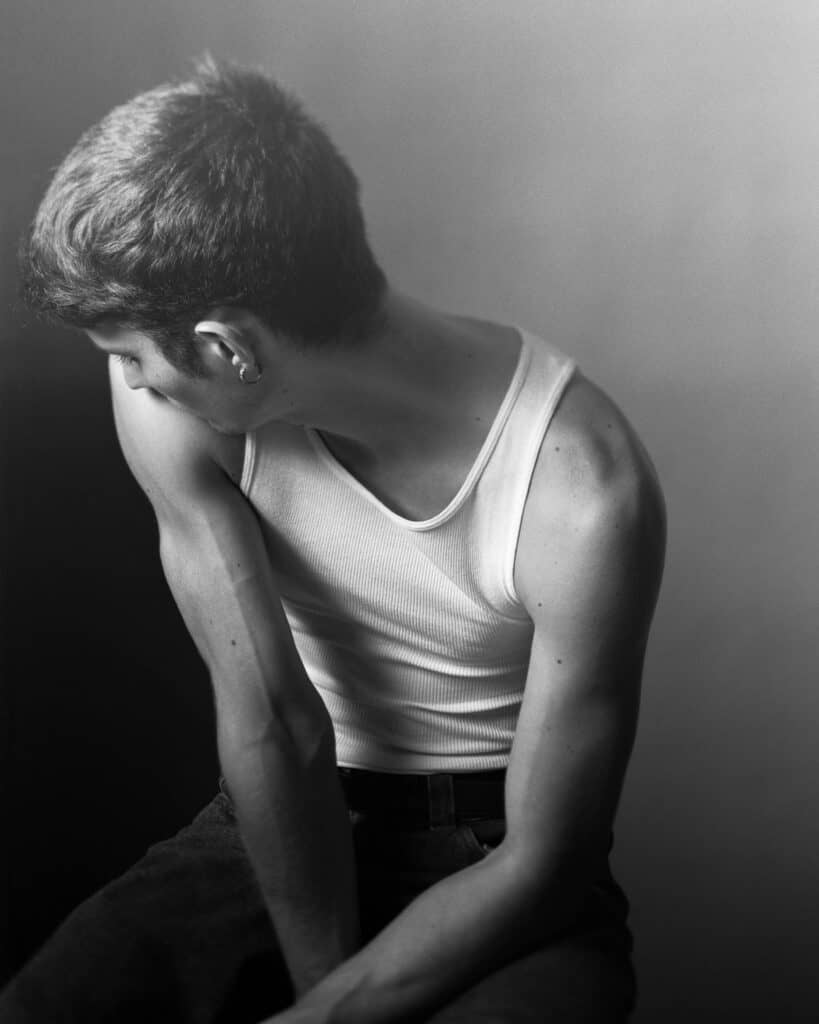

She directs Emile, telling him to turn his face, to look at the ceiling, to hug his knees, to close his eyes.

When the camera closes the shutter, the flash is almost imperceptible: something has happened, Victoria has just taken a picture, but that instant could well be mistaken for the blast coming through a window, fluttering everything.

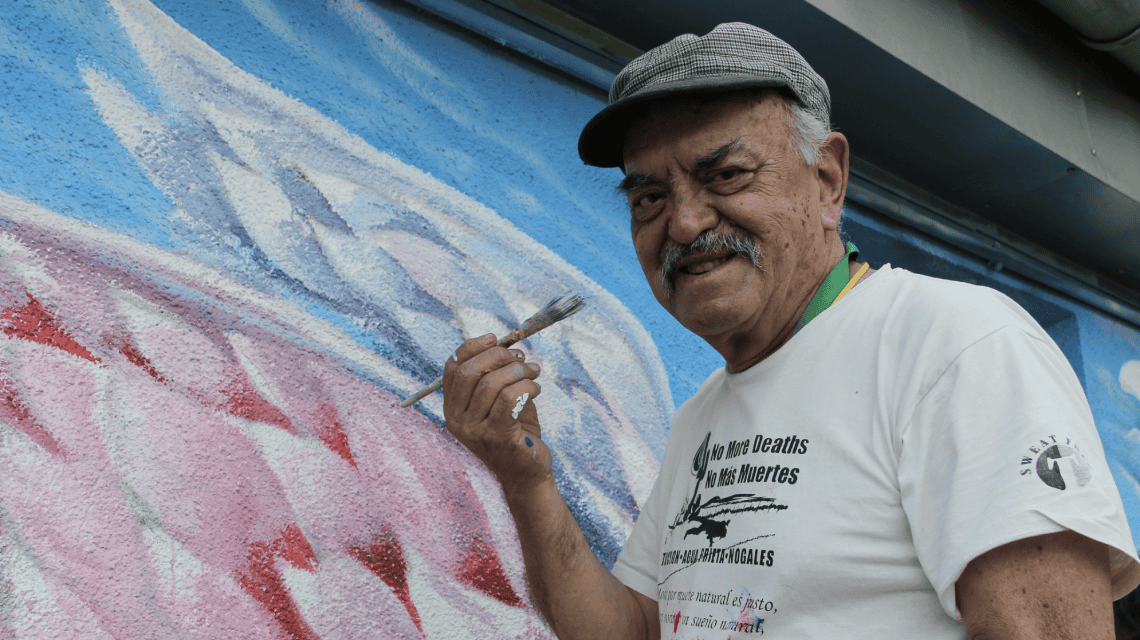

Victoria was born and raised in Brazil, surrounded by nature, by animals. Now she lives in New York and seeks to build her own boats with photography. Her house is full of cameras, of objects from all over the world; her walls are adorned with photographs of colleagues, of pencil drawings that reveal a past as an experienced artist that sometimes, but only sometimes, becomes present: Victoria’s house is an island made of other islands and a dog named Paco, who goes to his room when visitors arrive, because humans are not his thing.

While Emile remains barefoot and with his eyes closed on the couch, Victoria turns off the Hasselblad and holds it in her hands. She smiles. She lets those of us present know that there will be no more photos today. And she says it like an Oracle because Victoria’s voice is subdued but determined about everything.

Then she takes the camera to another of the islands, one full of cameras and lenses and film. She leaves it resting there, as on the other desk rests the boat tied to an imaginary anchor, waiting to sail again.

Then, he offers us a glass of Sake and we don’t refuse.

Sometimes drinking and accepting that for today there will be no more photos, is also a way to create and living with art.

***

I am never satisfied with my work, Victoria tells me in a shopping mall. She turns her back to the statue of Christopher Columbus that gives Columbus Circle its name and takes a sip of coffee while she talks to me about chance, which she prefers to call acaso. I point to a building that is barely visible behind the window and tell her that this is where The Little Prince was written. And then we talk about the morphology of Portuguese and I ask her to pronounce triste, and for a moment, believing that this will lead us to a new part of the interview, I share with her that it is my favorite word, thus, pronounced in Portuguese. But my venture fails and then Victoria tells me about the special relationship she forged with horses in her childhood.

And it is strange how the thread that begins when she talks about her relationship with animals (especially dogs and horses), leads her to New York, to talk to me about how her photographic career took off. Inevitably the event Victoria refers to is personified as she finishes her coffee: I started taking photos to interact with people, to get to know them better.

And then I remember the time when she directed Emile to take a portrait of him, and other times when I have witnessed how Victoria interacts with her models, and I think that what we see in her photos is an accurate reproduction of the tranquility that her presence generates next to the people she coexist with.

It’s not just her voice, it’s all her gestures, the movement of her arms tattooed with a 35mm film and a straight line, that are able to calm the water around the islands and tell us that all is well.

***

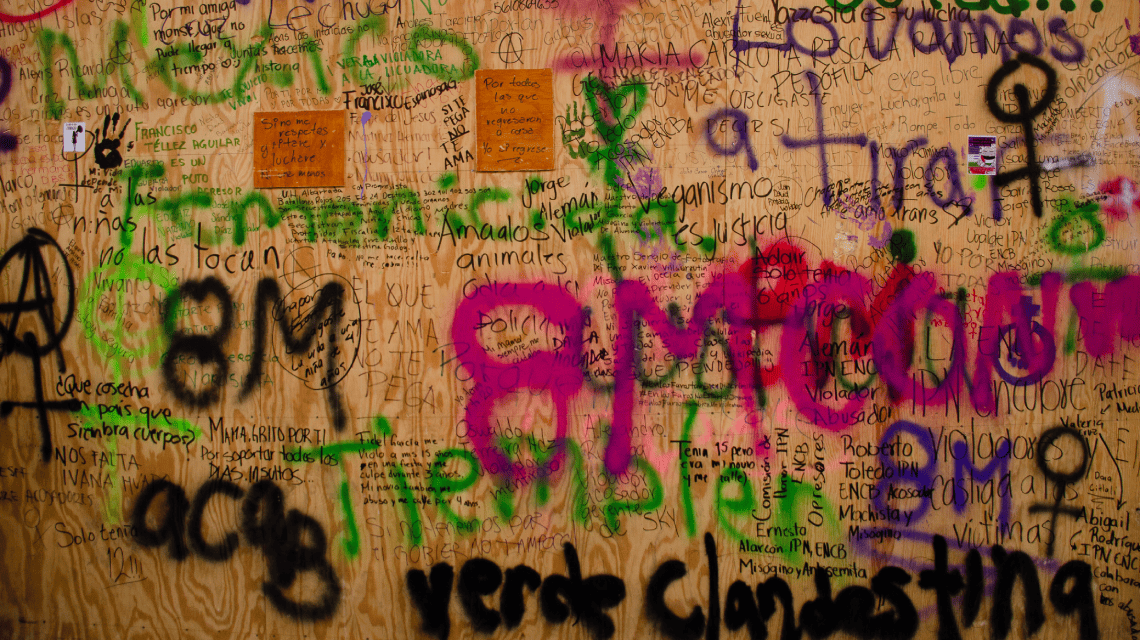

Last May 19, ‘Lifelines’, a joint exhibition at the International Center of Photography was inaugurated and in which Victoria participated alongside photographers from all over the world. The two photos she presented condense Victoria’s photographic work so far: a naked body submerged in another body of water in a wild, natural environment; a woman in a bathtub with wet hair: freedom, chance, acaso.

I look for myself in my portraits, I look for my own emotions in all of them.

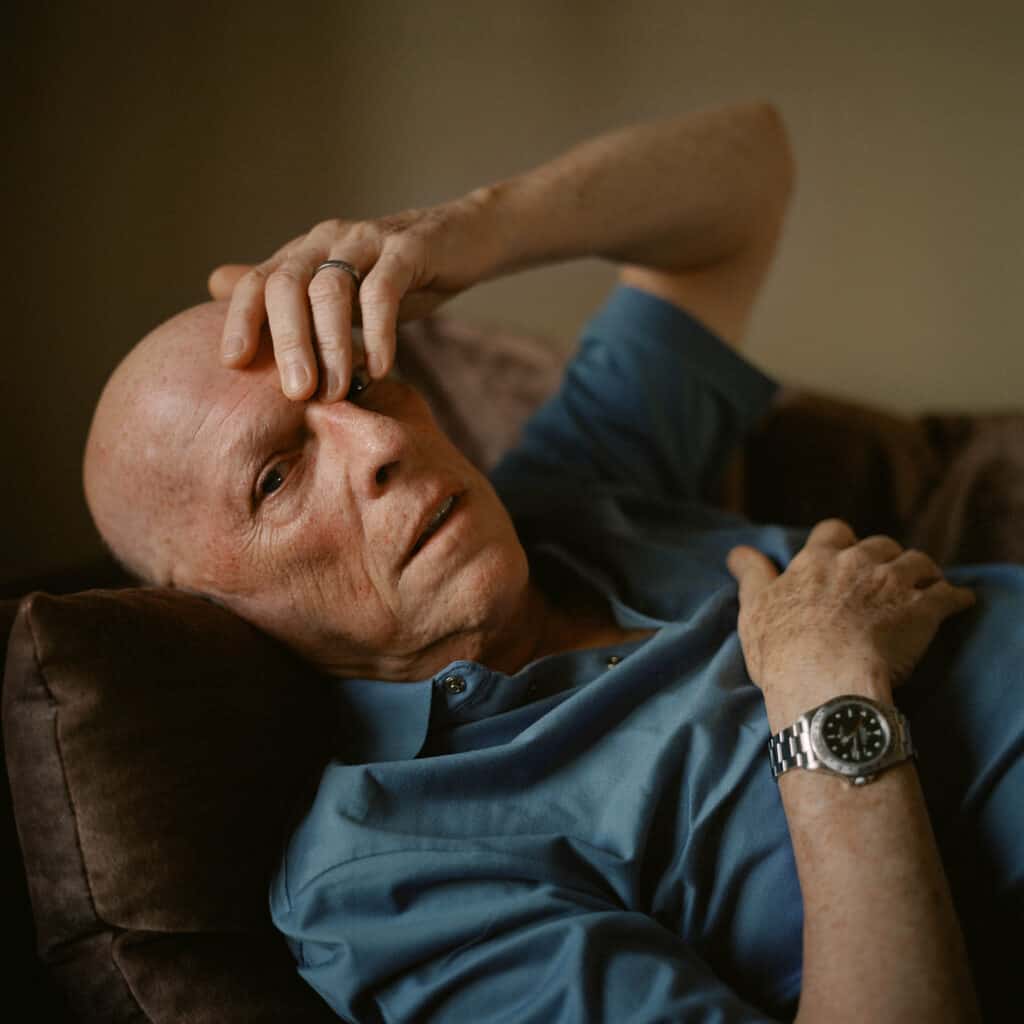

Then Victoria talks to me about loneliness. We get up from the table and start walking: there are tourists, ladies with expensive purses, a man shouting into the phone. I like solitude, but even though I like it so much, I never want to be alone.

And it’s interesting how, almost every time, her photos are of lonely people, just contemplating the atmosphere Victoria has created for them.

***

Victoria sings. Some of us clink our sake glasses, others talk, still, others play video games on a huge television. Photography rests for now. What does she sing, Victoria? She sings a song in Portuguese, but when she does, she makes an island within her own island. She sings Ellis Regina, then she sings Vinícius, then a song that was composed and recorded not far from where we are, from her apartment. And here, in the heart of her home, Victoria lives among her drawings, her photos, and the reflections of the people she has captured in her portraits.

Victoria is pure and latent sensitivity: I believe that sensitivity is a gift, but also, sometimes, it can become a sorrow.

The song ends, Victoria now sings Simon & Garfunkel. Suddenly I’m not here, I’m not on the Upper West Side, I’m not even in New York.

I’m going to an island, one of Victoria’s many islands, the kind she creates like when she builds little wooden boats.

Outside, in the real world, the afternoon dies. EP