It’s Friday night. It’s almost ten. The International Center of Photography on Manhattan’s Lower East Side seems to be completely empty, but a faint sound of running water coming from the lab indicates otherwise: someone is still there, developing, printing.

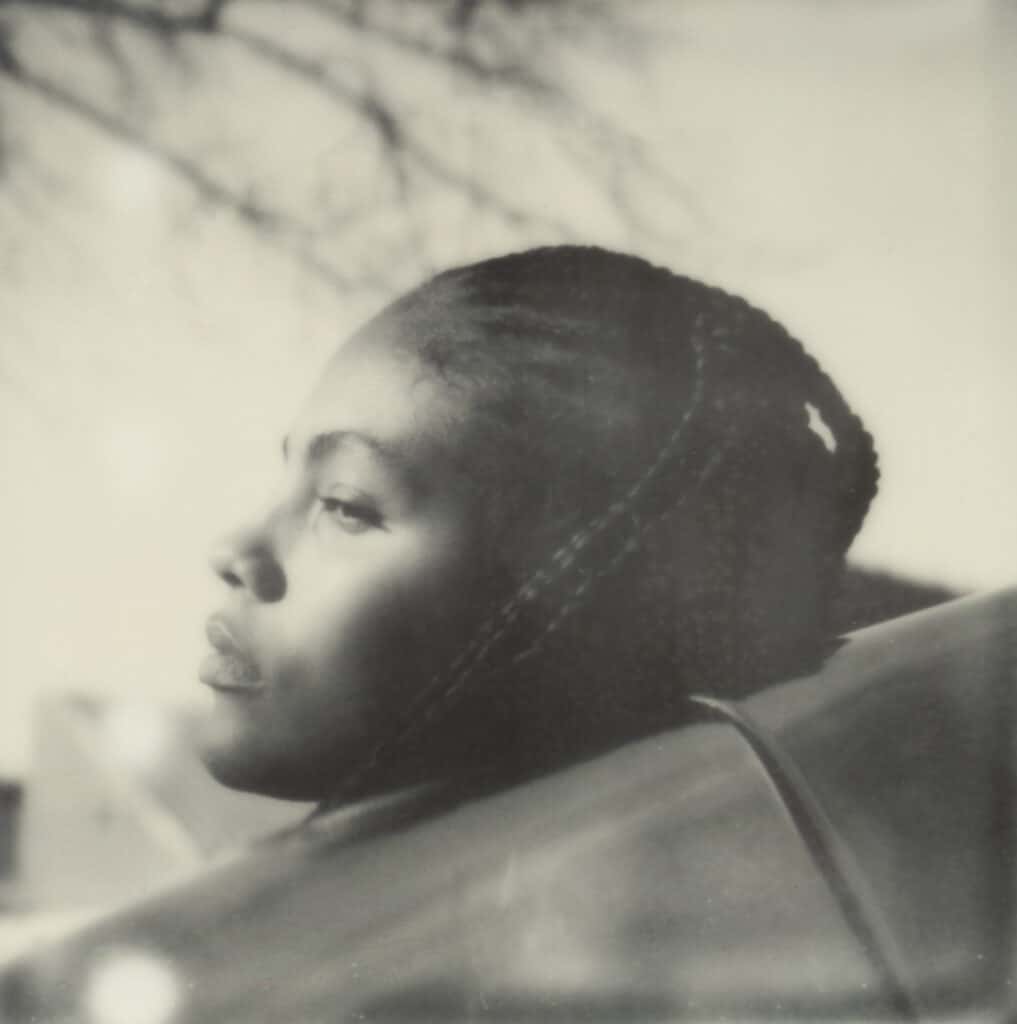

Roxane Moreau swims in the red darkness of the developing room between enlargers and aluminum sinks, with the same ease and precision as someone who plays a musical instrument with closed eyes. She repeats the process again and again: developer, stop bath, fixer. Then she steps out into the sterile light of the hallway with a plastic tray in her hands. She checks the print. She examines it. She brings her eyes closer to the fiber paper, and grimaces. She walks over to a huge tub full of water where she dips the sheet next to a few others.

As Roxane returns to the darkroom, the people in her photographs, who minutes ago were just projections, are left dancing in the transparent stillness, floating, waiting.

***

We’re sitting in a café on Broome Street, but soon we’ll be out of there.

A tiny Catrina made of palm (which she bought on her last trip to Mexico), dangles from her left ear and jingles as Roxane reaches her handbag to grab something. After finding it, she holds out her arm and hands it to me.

It’s her business card, right off the press: on one side, a black-and-white photo of her, wearing a Yankees uniform and cap, glove on, staring, getting ready to catch in the middle of a ballpark; on the back, some data in black letters: Nickname: Rox, Birth: Reunion Island, Camera: Mamiya 7, Favorite Photographer: Larry Sultan.

I recognize the irony: her business card, as explained by tiny letters under a QR that leads to her Instagram, is inspired by the set of cards that artist Mike Mandel made in 1975, which featured photographers like John Divola and Manuel Alvarez Bravo as baseball idols.

Roxane was born on Reunion Island in 1994, surrounded by strong women and a father who, without hesitation, she recognizes as the best cook on the island and the whole world. The granddaughter of immigrants who settled in North Africa, at the age of eight she was already taking her first photos with a small Canon that her parents gave her, the same year they took her and her sister on a road trip around Australia.

We’ve been traveling forever, so photography has always been there.

After sipping the last of what was left in her cup, she tells me about what she recognizes as her first act of rebellion and independence: I didn’t like anyone to dress me, I chose my own clothes since I was six years old.

She looks around and just says:

Shall we get out of here?

And off we go.

We leave the place and walk aimlessly. It is one of the sunniest and most pleasant days of February so far.

For Roxane Moreau, photography is nostalgia, but also rebellion. Rebellion against the urgency to create, against that banal idea that Artificial Intelligence has made of the act of creating, of the artist’s craft. But you only need to see her dancing in the darkroom to understand that analog photography, for her, is also magic: most of the time, inside the darkroom I feel like Merlin making potions.

We cross Delancey.

At the age of 18, Roxane moved to Paris to become a chef. She made her first cake when she was ten. So which came first, cooking or photography? I ask her. Photography, definitely, but cooking had a big impact on me. She worked for the best restaurants in Paris 13 hours a day, three jobs at a time. But there was something in that millimetric process of building magazine-cover desserts that prevented her from creating at all: I needed to create and cooking didn’t allow me to do it immediately.

Paris was an explosion, it was the realization that contrary to the cooking, through the photo, I could become the person I had not found anywhere: in the kitchen and in art, good people are underestimated.

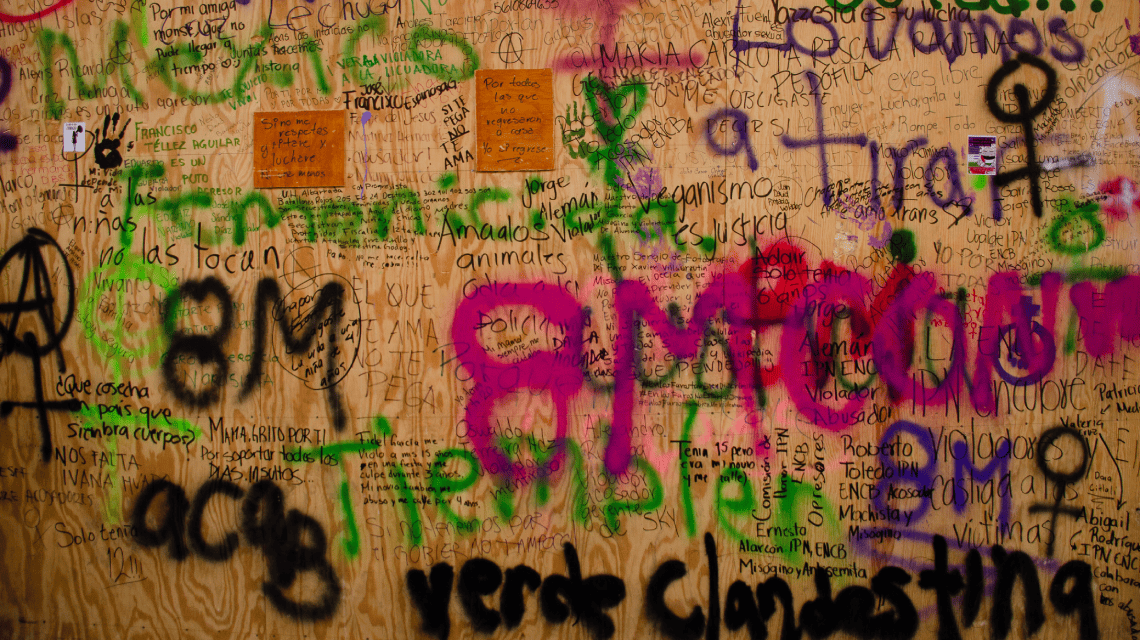

We walk north on Orchard Street and when we pass in front of Russ & Daughters, a Lower East Side icon, we go in. We sit at the bar. After ordering a coffee, Roxane pulls another item out of her bag: this time it’s a blue cardboard box with gold lettering that reads Tarot XXI. She opens it and takes out a deck of cards. It’s her photographic interpretation of a Tarot deck, everything that cooking once prevented her from doing, Roxane poured into this project.

Photography has been my most difficult relationship, she tells me, but my dreams are where it is, and today they are here in New York.

As she tells me about the admiration for starry skies she’s had since childhood, I shuffle the cards slowly, admiring the work on each one: characterization, makeup, lighting, and photography, of course. Only thirty were made, and today, the one I’m holding is the only piece Roxane has left.

In a few years, perhaps, this set of cards will be an influence for someone else, just as Mike Mandel’s cards were for Roxane.

Yes, photography is magic, I am sure that each negative, each print, keeps a part of us, she tells me, after I ask her about her predilection for print and for those objects, apparently docile, behind which lies all her rebelliousness. We, humans, destroy everything, but we have also created things as beautiful as the photographic process.

I ask Roxane which Tarot card best describes her, and without hesitation, she takes the deck out of my hands and starts looking. She arrives at card number XVIII, La lune, depicted by the double exposure of a pale woman on a black background.

The moon has two sides, one reflecting the sunlight and one which we cannot see.

***

The tranquility of the tub full of water is interrupted by Roxane’s hand. She pulls out her prints, one by one. Pictures of people, motley characters from everyday life in common situations, but whose features and poses, somehow, Roxane manages to mystify through her whole process.

With them in hand, she goes to a cabinet with drying trays. She lays down her fiber sheets, silent, her gaze still fixed. There they will rest, drying, until tomorrow, when Roxane arrives back at the ICP and finds them.

She puts her negatives in a black folder that she tucks into her handbag.

She puts on her coat.

We walk together to the elevator that will take us to the street. At the corner of Essex and Broome, we say goodbye, she reminds me that I’m going to Mexico and wishes me a good trip. In my headphones, a Joan Armatrading song begins to play as I watch her get lost in the crowd, heading for the subway entrance that will take her home in Brooklyn.

Then, something she told me that morning comes to mind:

Photography is not about us, photography is us. EP