So, you have to burn to ashes in order to rebuild?, I ask Raine, who pauses and looks at the street. She looks for something, perhaps the answer to my question in the pavement, in the bricks of the building across the street, in a dog that walks by and looks at us: Saturdays in the East Village feel like Sundays sometimes. She looks again at the table in front of her, at the Danish bread whose name we couldn’t pronounce, at the two half-empty coffee cups. She takes hers between her hands and takes a sip. Leans her body back on the metal chair and concludes: Yes, you have to lose everything to be able to rebuild.

Immediately and unconscious of the irony, she reforms her answer and adds: you have to lose everything in order to intentionally build.

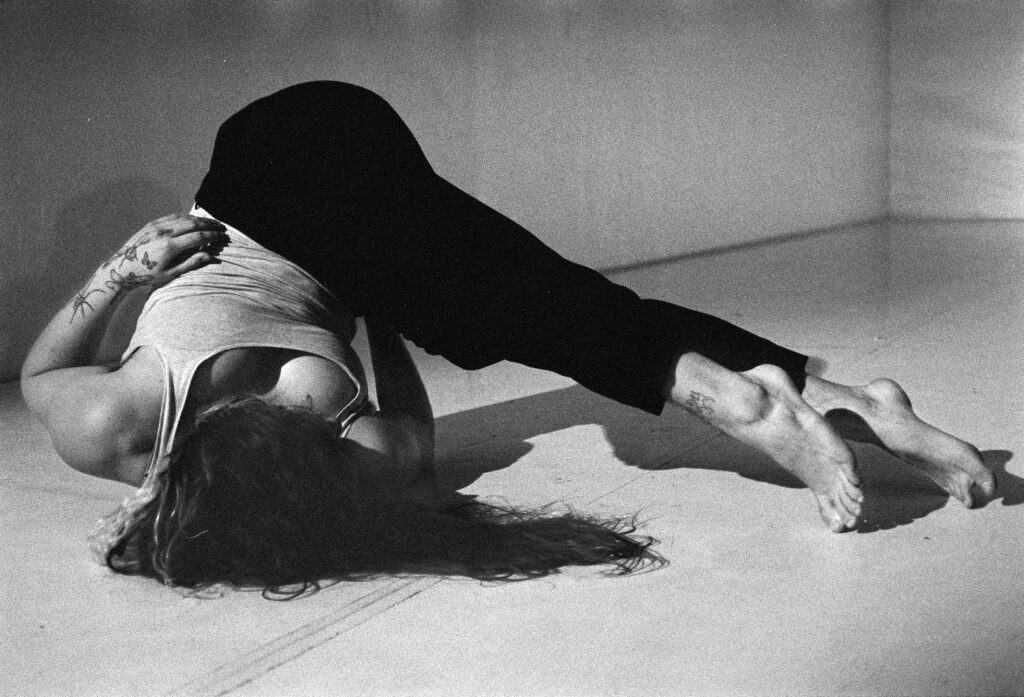

The first time I saw a photo of Raine Roberts was just a few meters away from here, in Emile Kees’ apartment. It was also Saturday and we had met for dinner. Earlier in the evening I saw the picture hanging next to a Noguchi poster. I thought I recognized it from some book or exhibition: a woman lying on a wavy public bench, near the sea. Try as I might my memory couldn’t guess where I had seen it, until before we left someone asked: isn’t that Raine’s picture?

She herself, unwittingly, describes to me that image of a woman sunbathing at Coney Island when we talk about what she looks for in the world when she holds a camera: structure, routine, rhythms.

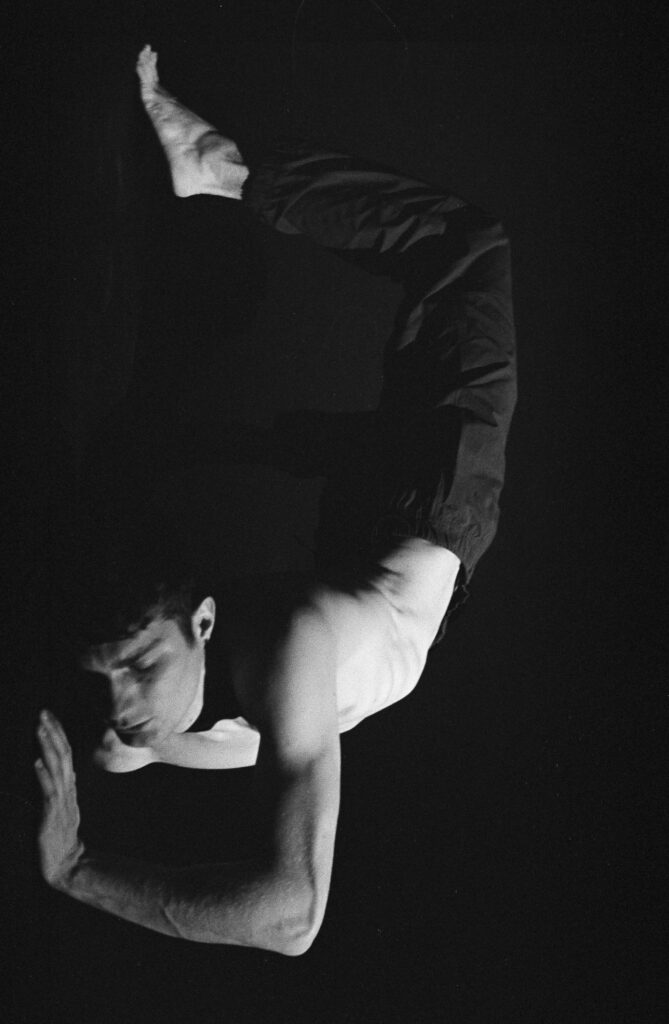

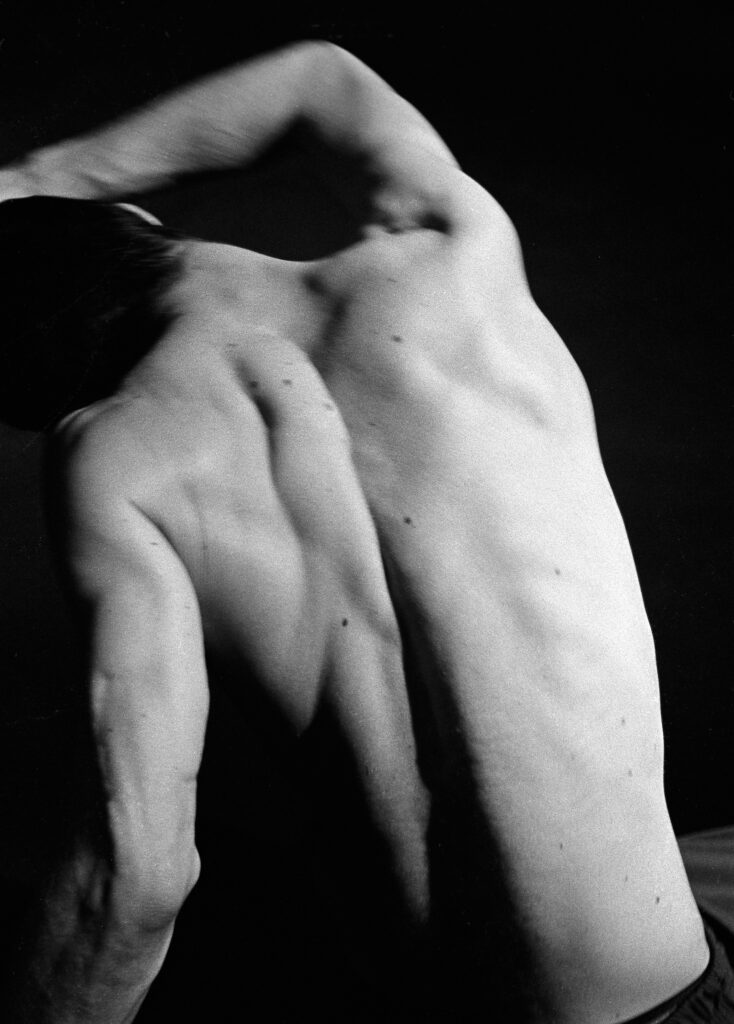

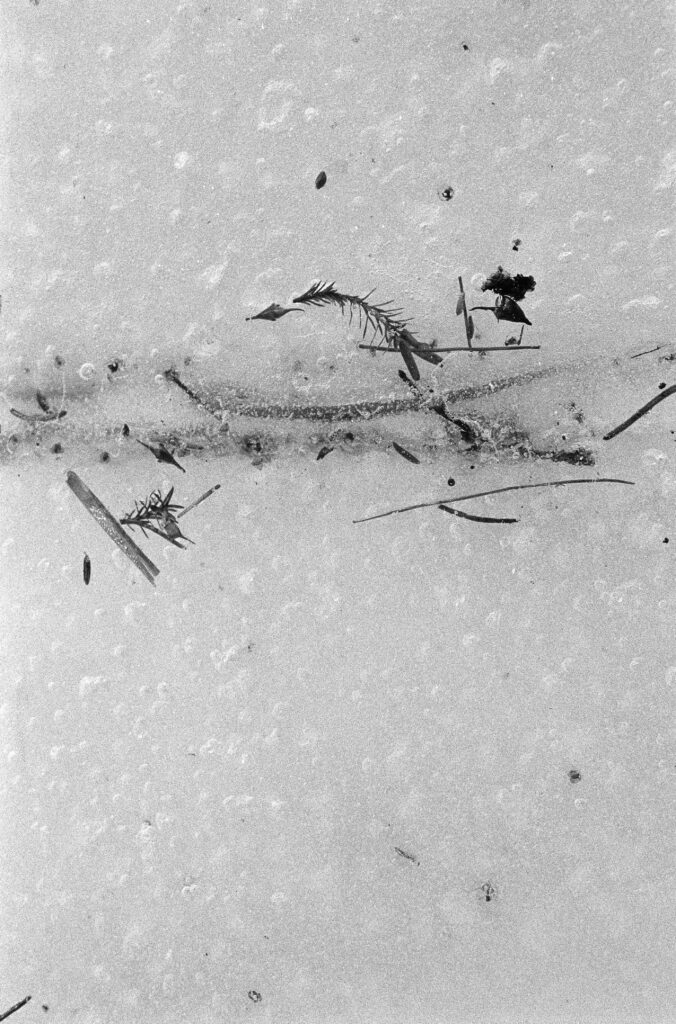

Raine was born and raised in Chicago in the mid-nineties and somehow, whoever stands in front of one of her photos will be able to glimpse limits and geometries, conjugations of artificial and superimposed lines interacting with dimensions (her own and the artist’s) and light: the whole city contained in an image, even when there are only human bodies over darkness; the absence of color is the confirmation of that monochromatic discourse that Raine builds between sentences, little by little, as spaces are built, while she talks to me on this 12th Street sidewalk turned into a terrace: I have been redrawing my limits, they were very blurred before.

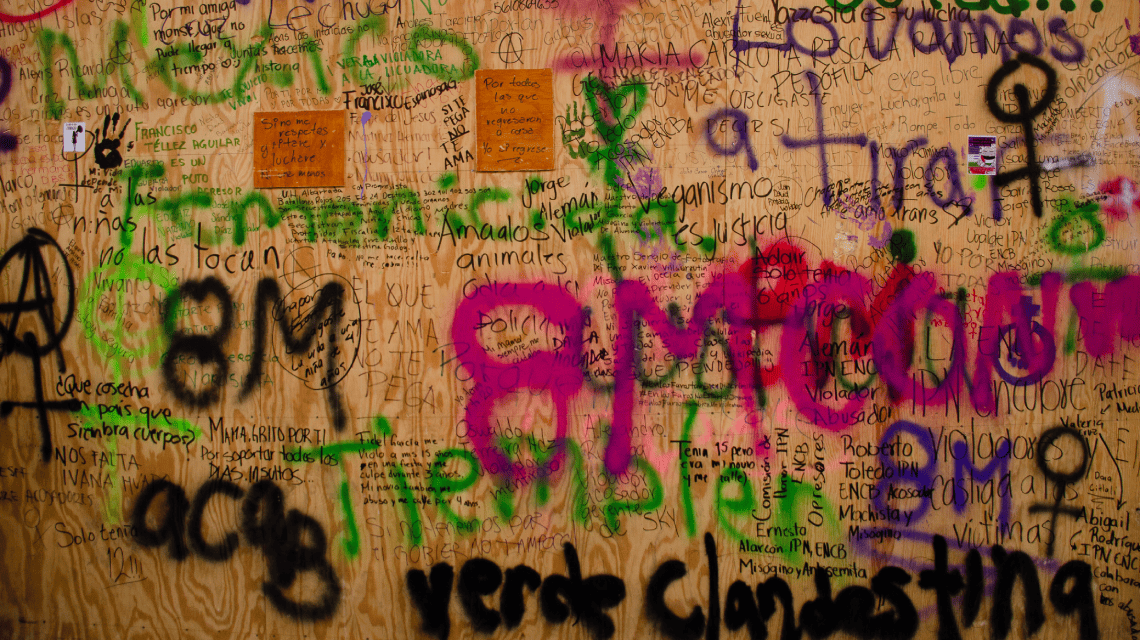

For Raine, photography is energy, perspective, intention, the same intention with which Chicago was rebuilt after the great fire of 1871, then, borders are that we draw voluntarily, after what was there, no longer is.

Cinema was the door to photography, but I must say that before, my life was soccer, she tells me, when I ask her if she sees any parallels between her photographic practice and the sport she has been playing since she was a child. And suddenly there is a moment when we both burst out laughing, because I was also a goalkeeper, the only difference is that Raine is still playing to this day. And the fact is that, despite the unpopularity of those of us who once played this position, to be a goalkeeper you have to be a great observer. Raine, far from the days when she would do somersaults when the opposing team was far from her area, continues to find in soccer the necessary balance of his artistic life.

***

It is early January. Writer and curator David Campany speaks inside a room at the International Center of Photography, lit only by the luminescent embers of a projector. After introducing himself as writer/curator/editor/educator, Campany makes it clear to the 12 photographers in front of him that the most important part of how he defines himself is not in those words, but in the line that separates them: the diagonals. Across the table, in the darkness, I see Raine nod and then write something in her notebook.

Now, as we talk about the excessive categorization with which we have to self-define ourselves most of the time, especially in the tiny spaces that social networks offer us to present ourselves to the world, Raine recalls that moment from David’s workshop and tells me, while emulating diagonals with a gesture of her hands: we must embrace our diagonals, that’s where our unique qualities lie. We must embrace our weirdness, our mistakes.

Because in addition to abstract black and white photography, Raine also writes poems, keeps a diary, and is a videographer. When she tells me how, in between her work as a video editor for a New York studio, she found the time to make her own montages with archival images, I think of the tomboyesque teenager who used to make somersaults to entertain herself while the game was being decided far from her goal.

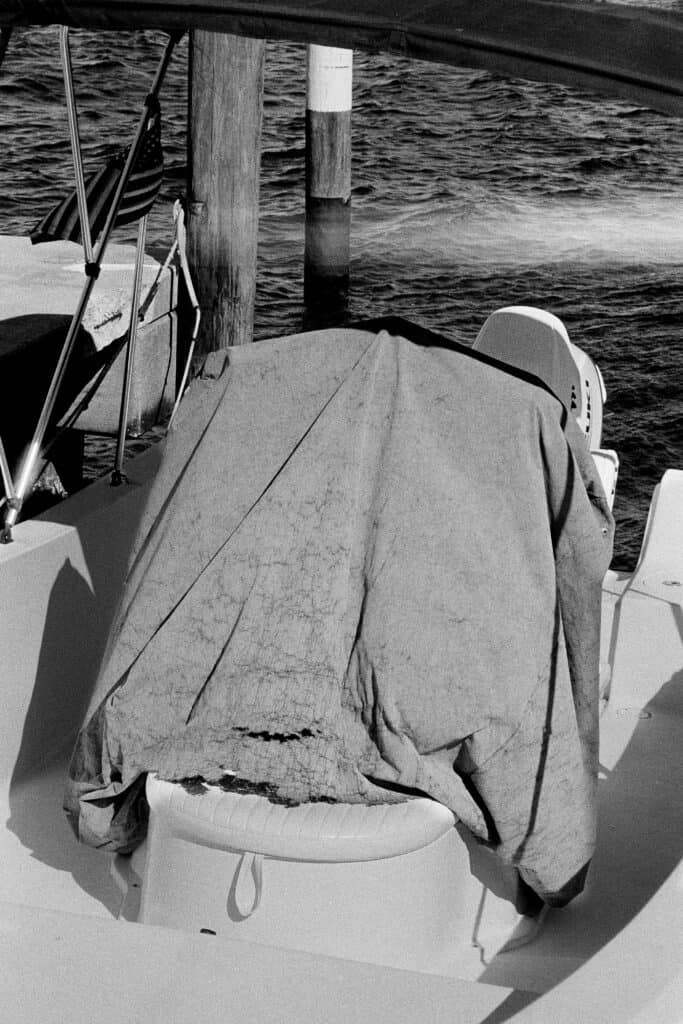

Those video cuts, or Raine’s Archival Collection, are riddled with archival images with some defect, typical of when digitization began to dominate the world and the interfaces understood as little as we do. And it is these unique defects that Raine also seeks in the texture of photographic film, that process that she defines as purely human: I think we have an identity crisis, and it is in imperfections that we find ourselves.

Raine could have been an architect. She doesn’t mind the idea. And she gets excited when we talk about the architecture around her, just as she does when we talk about the first time she fell in love. Her photography searches for lines and meaning in the frontiers of dimensions. Photography is architecture, too: photography is a place, a space, like this plate and this table and this stool, or this involuntary ceiling created by the scaffolding with which the building in which this café is located hides its reconstruction.

Color distracts me sometimes, I only use it when I photograph someone very close to me. As we get up, he holds out his cell phone and shows me a color portrait he took of Brazilian musician Nathan Dies. We walk away from 12th Street as we talk about how in the corruptibility of visual media, lies the most genuine of its practice. We get into the rhythm and structures of Avenue A and ironically, the only thing we talk about is color and the trip to Greece she took a year ago, in which all the photos she took were, contrary to what she does now, we’re only with color film.

As we weave through the pedestrian lines of St. Marks, Raine tells me that above all else, I recognize myself the most when I take photographs.

I just want things to make sense to me. EP