The airplane floats over the infinite amber rug that is Mexico City when seen at night, from the sky. María leans her forehead against the window and looks at rivers of red lights, amorphous buildings that get bigger and bigger. This reality, accentuated by that false slowness we feel when flying, seemed far away the night before when we saw the silhouette of Manhattan appear between the rusted iron of the Williamsburg Bridge from the subway on our way home.

Maria came to Mexico to continue a project that has no name yet but has been in her head for months. Tomorrow, not even twelve hours will have passed since this landing and she will be already with her Hasselblad on her shoulder, searching, revisiting every corner of the house she grew up in.

***

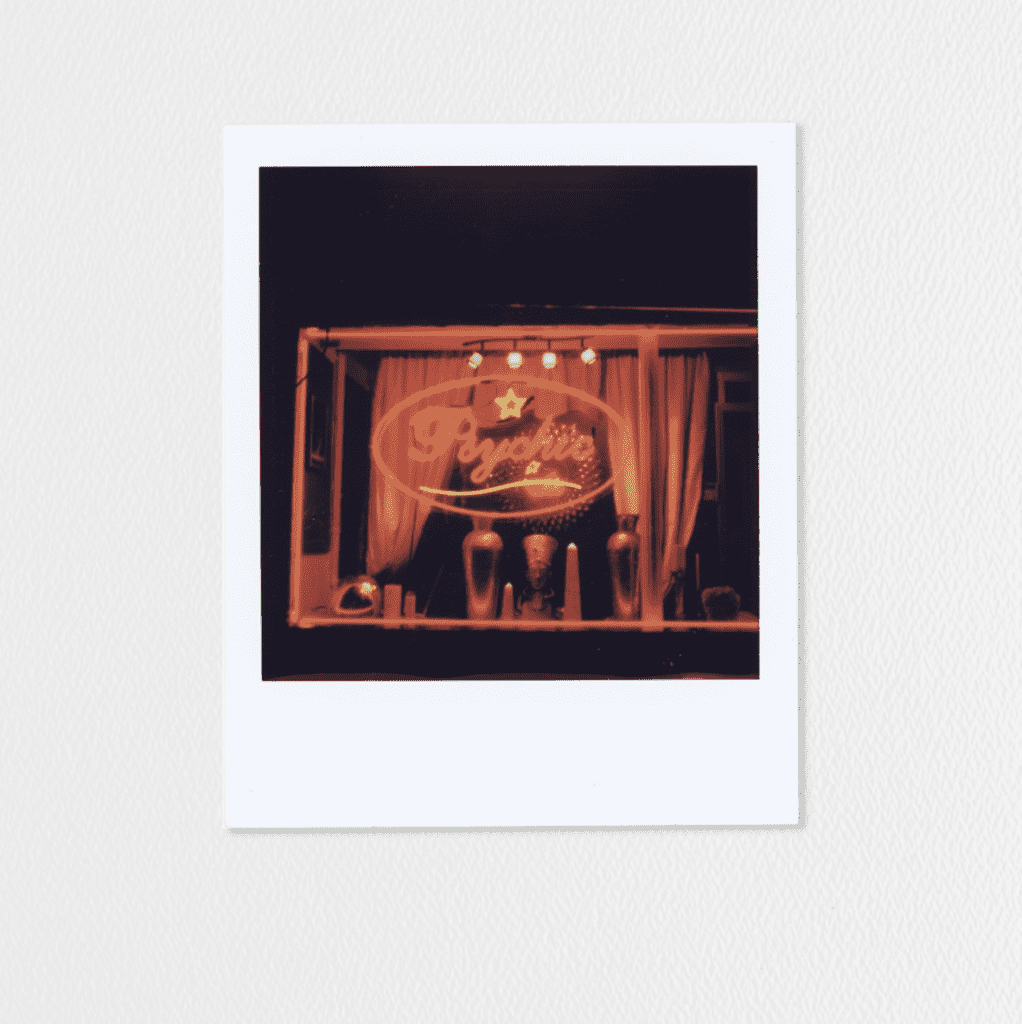

I met Maria with a Polaroid 600 in my hands. It was our last year of university and we had many dreams and very few certainties: we didn’t know that a pandemic was coming, we didn’t know that there would be three eclipses, we didn’t know that New York would be the answer to almost all our questions.

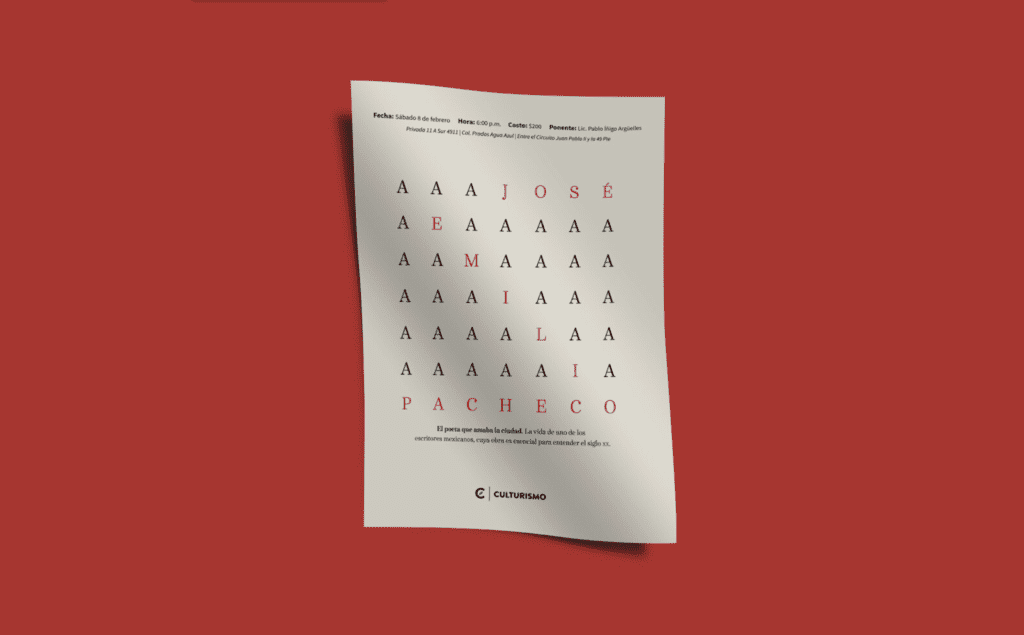

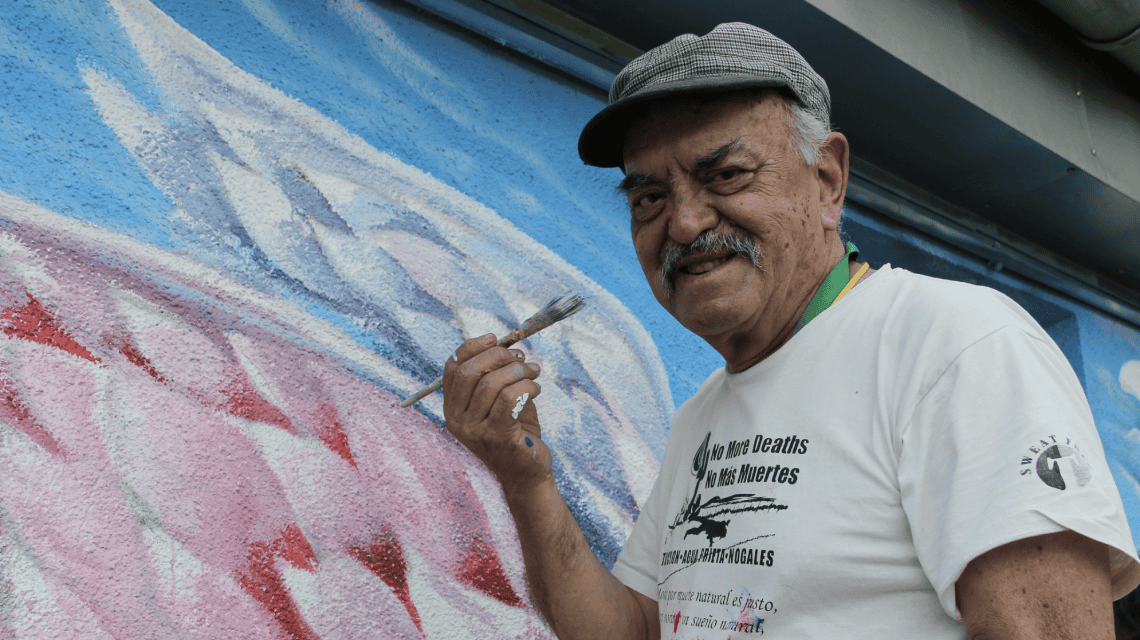

I remember her in love with Vicente Rojo, Gloria Fuertes and Andy Warhol, in that order. In fact, it was while looking at a display case with all the books designed by Rojo in an exhibition of his work at the Chapel of Art, that I heard her say, for the first time, that this is what she wanted to dedicate her whole life to.

She was born in Puebla in 1994 and still remembers the first photo she took: it was a Polaroid I took when I was five years old. My dad had planted a tree on the sidewalk in front of my grandmother’s house and it was quite an event. In fact, that same camera with which he took his first photo and which he had when we met, is the same one with which he sometimes goes around New York catching surreal scenes, letters, signs, lights, because reading the street, appreciating its intrinsic chaos, is one of his greatest obsessions.

And there is something about them, he tells me, they are perfect: there is nothing more perfect than a Polaroid. It’s the only way to make an object about a moment immediately and hold it in your hands. Tell me, what else in the world allows you to do that? And when she talks about instant photography she also tells me about the importance of the white space underneath each one: it’s not only where the chemicals are kept, crushed by a roller that spreads the emulsion, but it’s where all its possibilities live.

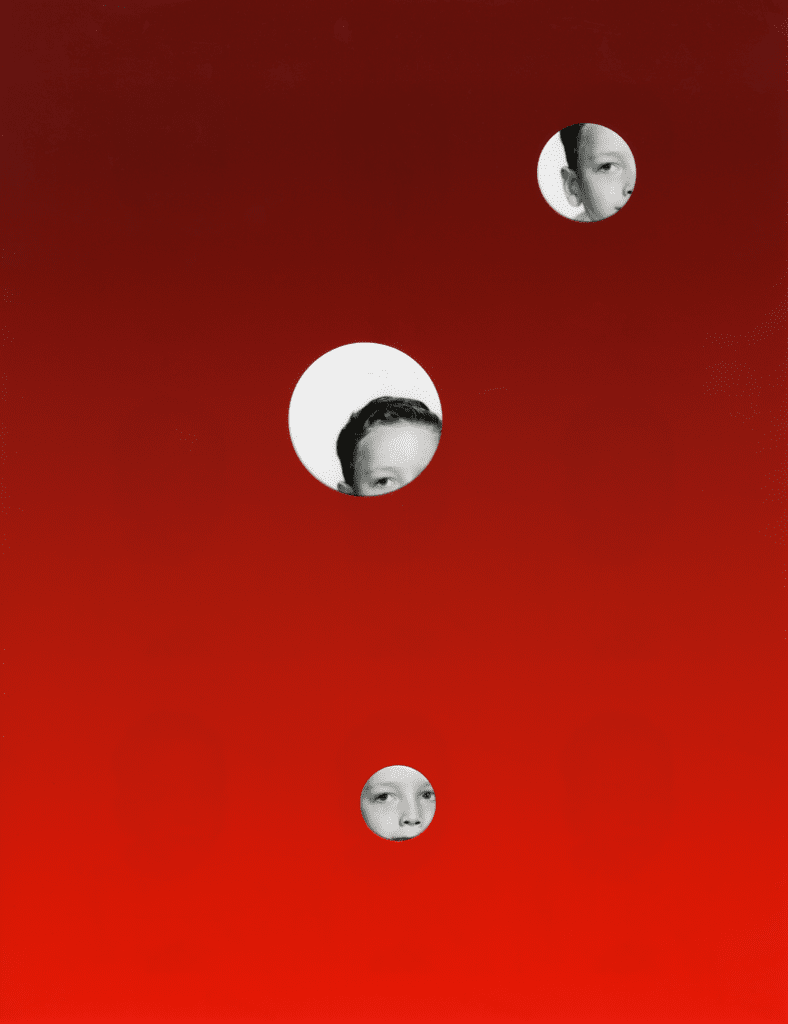

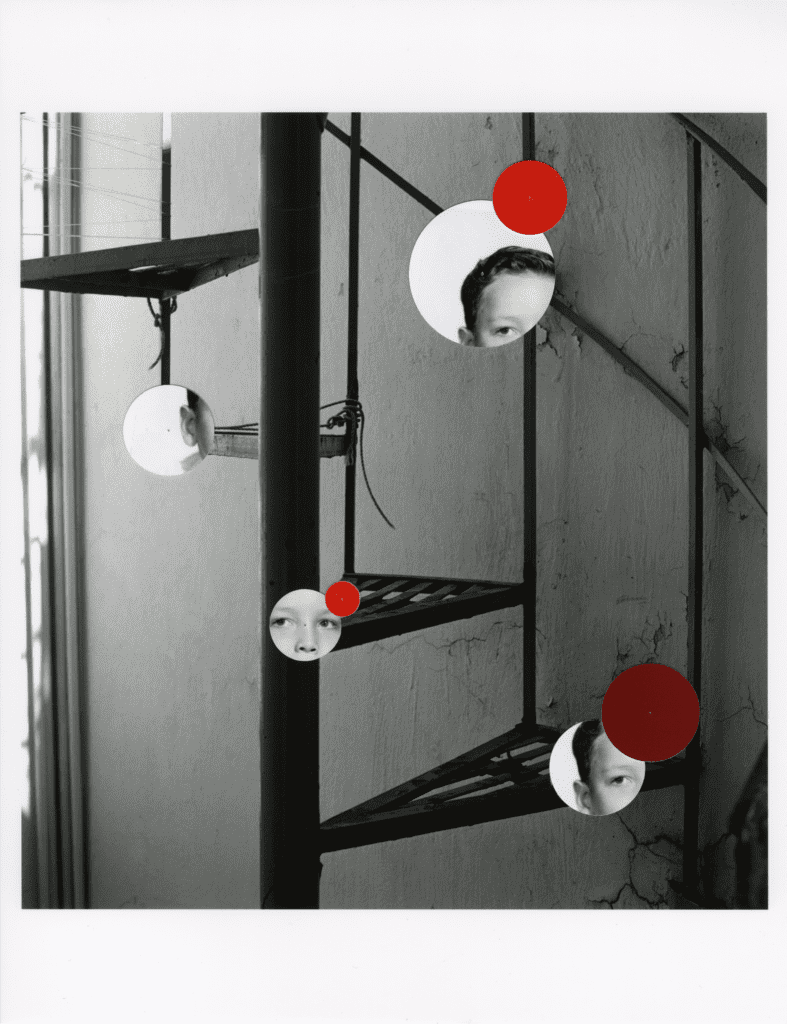

Maria, since she was a child, wrote captions and titles in that white space as if to never forget them, as if to name them eternally, something like Perseus in José Emilio Pacheco’s “The Blood of Medusa”, who “spends his days trying to capture the dust suspended in a ray of light”.

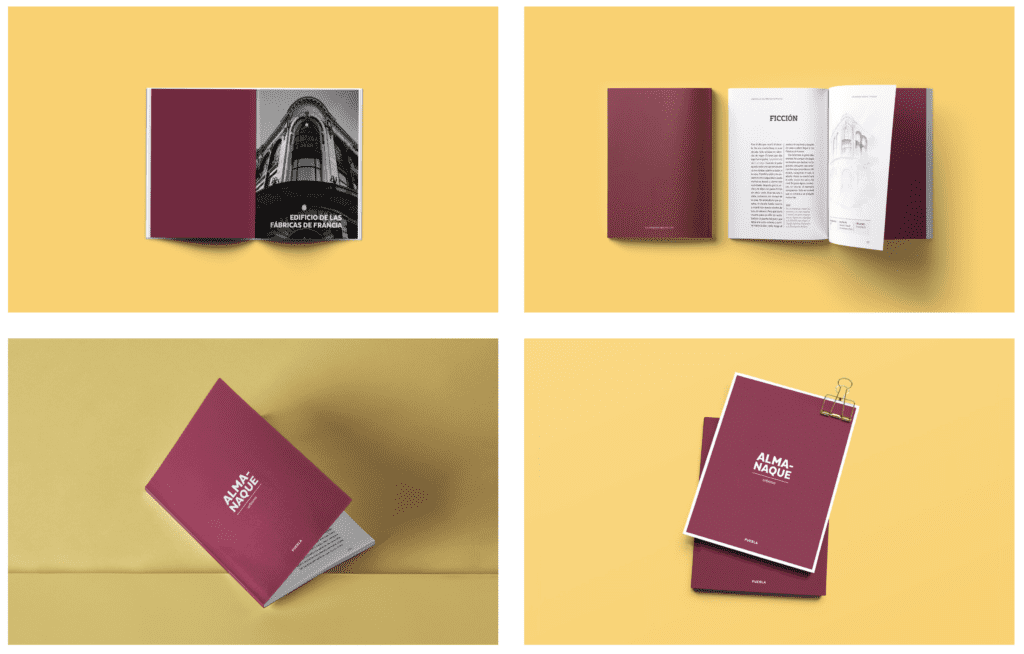

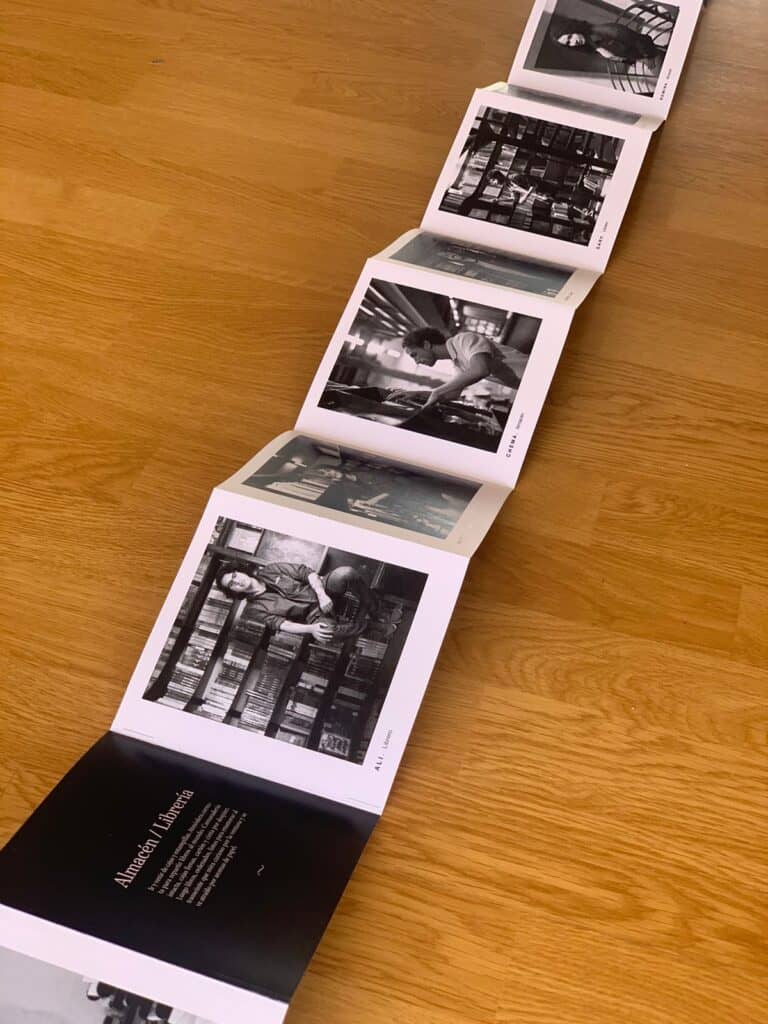

And that same passion, the one of letters imprisoned in white spaces, is the one that also contains her affection for boxes, especially one from Olinalá that her maternal grandmother gave her and that still smells of linalogue and photographic chemicals: María loves boxes as much or more than what they contain. In fact, she herself explains her fixation for them when on the way to Puebla I ask her what is the ideal way she would like to combine her photographic work with editorial design: everything is boxes, the books, the cameras, the photos, the texts. Everyone likes to keep everything and put it in boxes, even if they don’t realize it.

María cried the night Vicente Rojo died. We were in the car when we read a Whatsapp from Selva Hernández. And the fact is that we would never have been the ones Selva would have thought to tell first about Vicente Rojo’s death if only a day before we had not been with her in her bookstore in La Condesa, looking in wonder at one of the few remaining copies of Octavio Paz’s Discos Visuales, while we ate cake for María’s birthday.

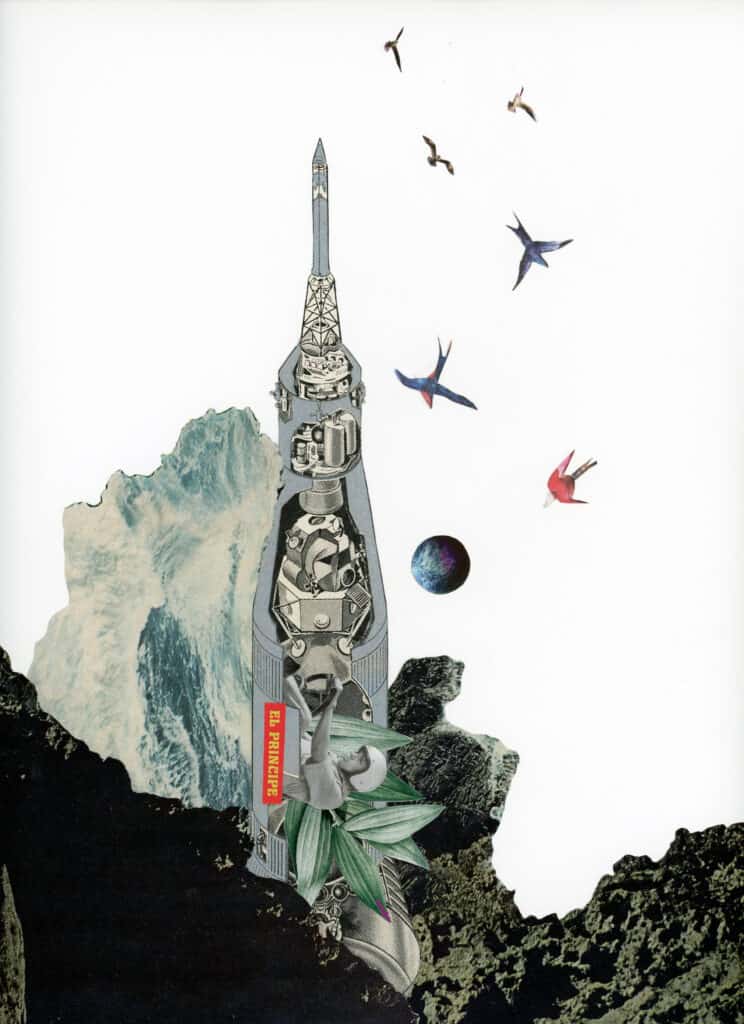

From Rojo’s work, she tells me, she has learned that the best design is the one that cannot be seen, that design is better when it does not exist, and just as many define Vicente’s work, María Prieto’s work also encompasses many geographies. There, among the latitudes that demarcate her, there between photography, design, Warhol’s tomb in Pittsburgh, Gloria Fuertes’ house in Madrid, chemical printing (which in recent months has made her spend more time in the darkroom than ever before), there is one that condenses all the others: catching clippings, saving them, arranging them, putting them on the table, making them talk, making collages.

Maria believes she is the opposite of the saying that you have to take thousands of photos to have just one good one. In fact, a roll of film can remain in one of her cameras for months: in the time I have spent in New York I have confirmed what I always thought about the photo, but was not always sure to say. You don’t have to take it superficially, you have to think about each one as you think about a book, a collage or a painting.

That necessary meditation, that preparation, that thoughtfulness, is what coexists with the chaos of Proyecto Análogo, the project that we founded together seven years ago and that María named sitting in the kitchen of her house.

***

We are in a room full of cages.

Her grandmother’s house, built in the sixties, saw Maria’s happiest years. Today, that green box at the foot of a tree-lined avenue contains all her memories, some more difficult to let go of than others, but to which the photograph has ineluctably led her back.

And not only to recall them but to understand them, to meditate on them and to arrange them as one arranges the clippings in a box of olinalá, to then spread them on the table and make them converse.

Her orange shoes and a colorful sweater contrast with the dusty floor, with objects from other lives. Maria notices the corners, the corners of the walls, the overgrown grass in the garden. She sets up the Hasselblad, focuses. She takes a while to decide whether to take the picture or not. And I see it: it’s not indecision. It’s not indecision at all. It’s just her natural search for the perfect through what is not and never will be: dust, chemical emulsions, time, love.

A week later Maria will return to New York with a box of medium format negatives in her carry-on bag. The project she has been working on for months will remain nameless.

Or maybe it already does, but we don’t know that.

Not yet. EP