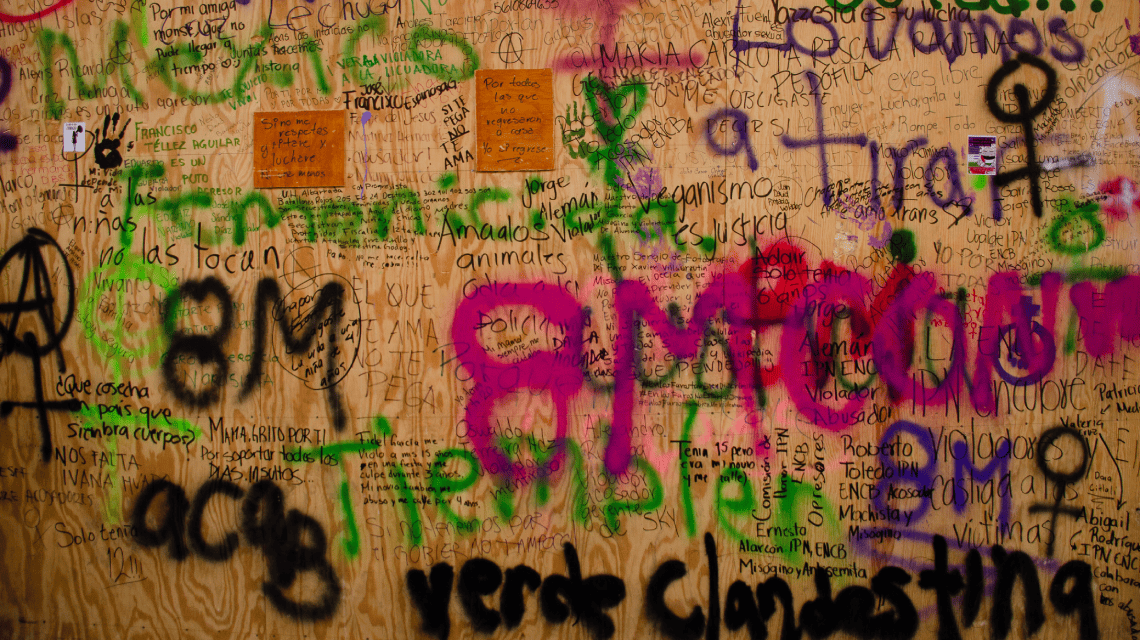

Where was I going with this? she asks herself from time to time, and then resumes the thread of the conversation or starts another one, or goes back to the beginning: talking to Flor means having dozens of simultaneous conversations, navigating the nostalgia of her childhood in Punta del Diablo, traveling to southern Africa, revisiting the light of a Roman window, analyzing the bifurcations brought by Maine and measuring, in adjectives, the rambla of Montevideo: their stories are coupled between melancholy and humor, converge with each other, as do the currents of the East River in this humid and uncertain New York Monday.

And the photograph, I ask her, where is photography in all this?

Photography?, asks outloud while watching the rain fall into Whyte Avenue:

Photography, for me, is all that’s left.

***

Flor Crosta arrived to Brooklyn with only the essentials: her favorite lamp, a photo of her with her brother and a small picture painted by Fefa, her friend:

I never had the dream of coming to New York but if not here, where?

New York, she says as she pours water from a glass bottle without taking her eyes off the street, doesn’t have what I like most about Uruguay but Uruguay doesn’t have what I like most about New York: the melting pot, that’s why I came.

Flor grew up with the sea in many ways. She learned to swim in it because she was allergic to chlorine and later found in surfing the freedom that would take her to so many places. The first thing I did when I arrived from Uruguay was to look for a place to live near the river and when I chose Williamsburg, as much as I walked and walked towards the East River, it seemed to get farther and farther away from me. This city has a very different relationship with the water, she tells me, as if coming to a conclusion of something she had been mulling over for months.

But let’s talk about uncertainty:

If it hadn’t been for the fact that on March 12, 2020, the world went into lockdown, Flor Crosta would be, perhaps, in Australia, doing something completely different, raising kiwis or something. Today, three years after the beginning of the pandemic, Flor meditates in a café in Williamsburg on what the pandemic left her, the paths it made her take and how she learned to make peace with doubts and lack of certainty.

For those who see the world through a lens, uncertainty is as necessary as those who search for waves in the sea: when all was lost, photography, for Flor, was the only thing that remained.

Her first contact with photography, she recalls (and this precedes a laugh), was a 35 mm Pokemon camera with which she recorded summers in Punta del Diablo and family trips. I’ve always liked the collective aspect of photography, I like its storytelling quality,” she says as she holds out her phone to show me the photos that a Google search showed when she looked for her childhood camera.

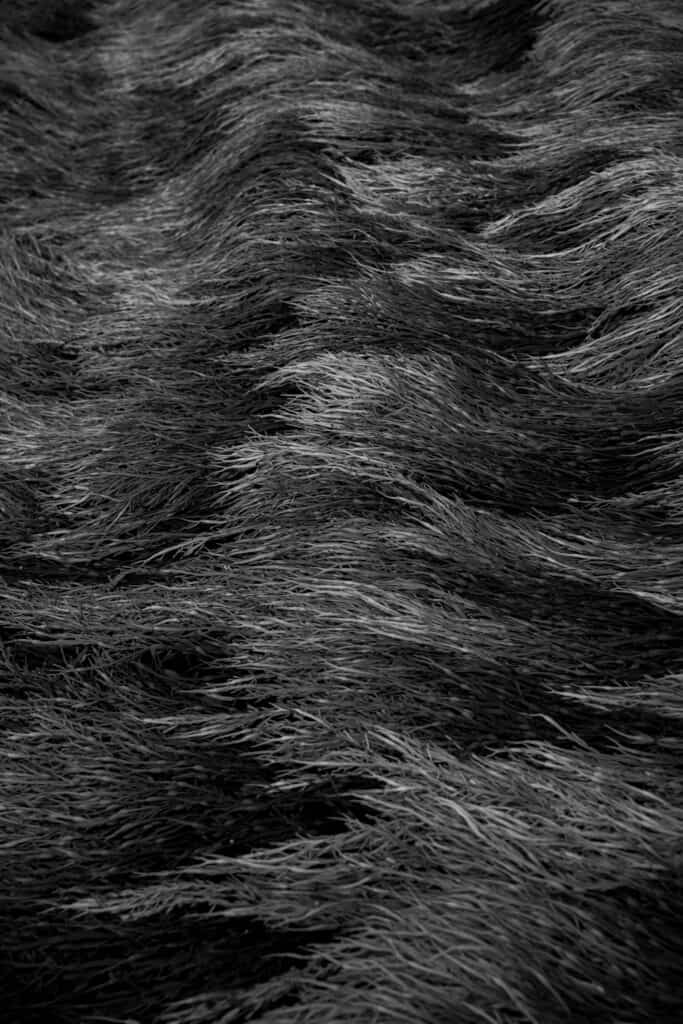

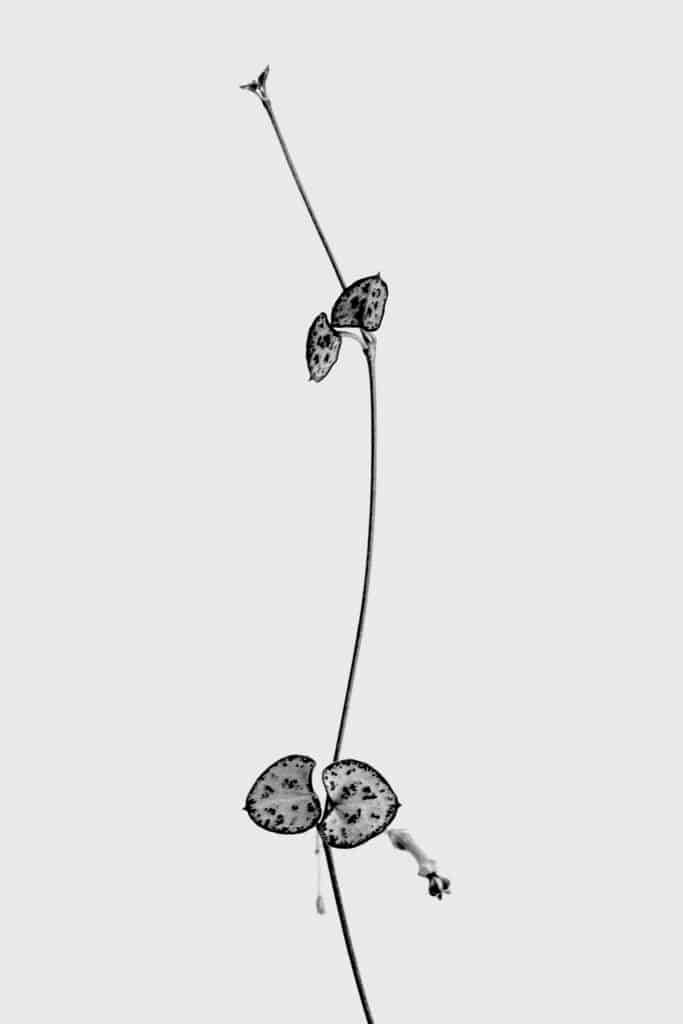

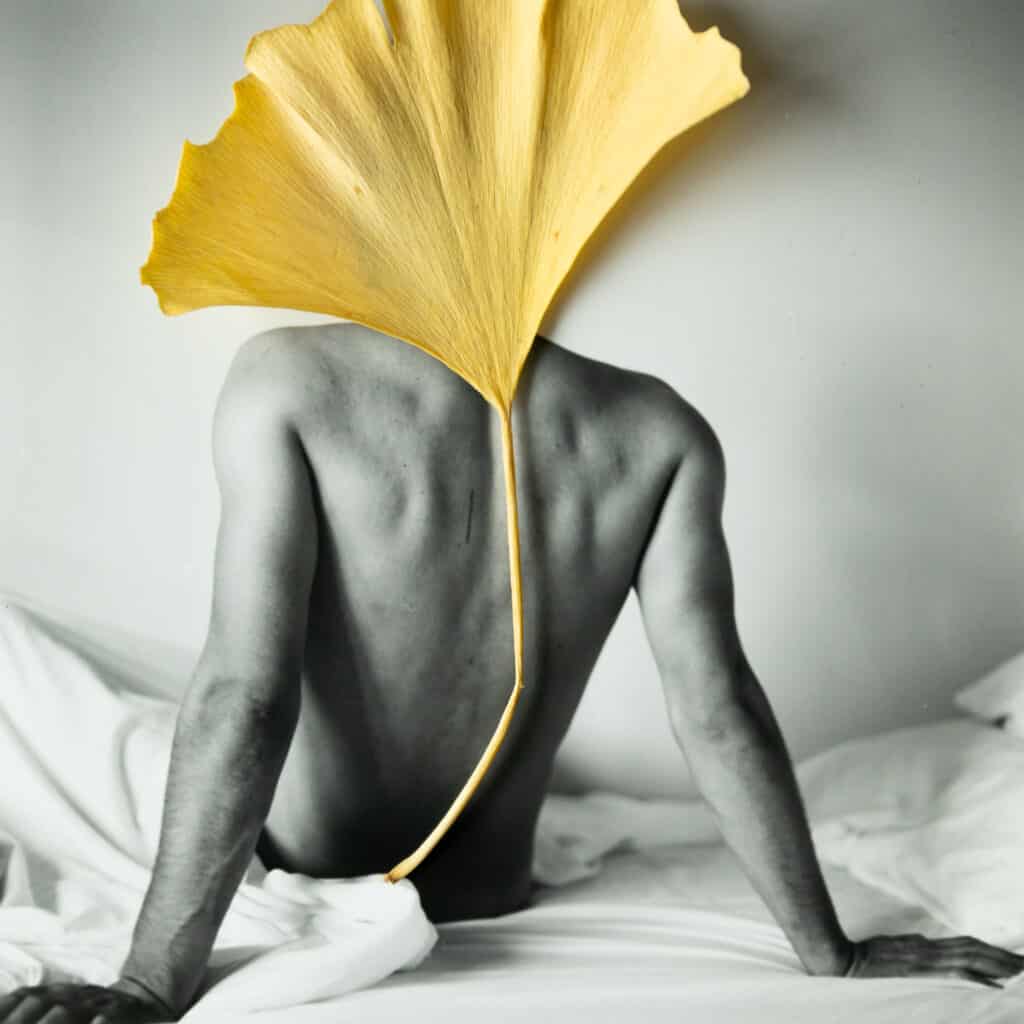

And what story does that series of black and white photos at the sea really tell, I ask her, remembering those slow-exposure photos of a group of women playing with the wind and dancing in front of the sea on a moonlit night: the nudity, the sea. That time I simply took the photos without planning them. I think that’s when things work best for me, when I just let them be and that’s it.

***

The bottle of water on the table is almost empty as Flor tells me the story of her Argentine grandparents, how her parents met and her paternal grandmother, who rented furniture to diplomats from various countries who came to live in Montevideo.

Furniture has always been, in some way, part of his life. Together with her mother, she started a line of antique furniture restoration that led her to appreciate more closely the function and versatility of objects, and how they can tell the story of the time in which they were intended. And it is, perhaps for that reason, that in a medium format Hasselblad, Flor finds the best medium to tell her own story: that camera is like a portable mid-century piece of furniture.

Flor could be a doctor, or an interior designer, or a flight attendant, as most vocational tests predict, but it is her coming and going of ideas, her paths found, the same that her photography offers to those who appreciate the connections and the worlds within them.

I am the way I am. I prefer to be good with myself first and then be successful, she tells me when talking about competition in the photographic world: I don’t like competition, if they like the way I am, doors will open for me.

That’s de point, I think, where her images are built, where her dialogue begins: determination, uncertainty.

***

We ride the F train to the Lower East Side. Flor knows her way by heart from Williamsburg to Manhattan: she knows exactly where to stand so that when the subway arrives and the operator opens the doors, she will be the first to enter the car. And then she says to me:

I’m happy where I am because I know I will leave someday.

She says this after being the first to sit in the light blue seat without divisions. Are you happy where you are because you know you’re going to leave someday?, I ask her, to which she only nods, with the same ambiguity as the end points when closing a story or starting, without wanting to, a new one, as if in the midst of the jumble of tides and ideas, arriving and then leaving, is the only thing Flor is certain of. EP