Emile Kees’ life is a succession of territories. Or at least that’s what I imagine as he shuffles around his East Village apartment, telling me about all the times he’s moved, all the homes he’s lived in, and everything he’s had to let go of over the course of his twenty-eight years of existence.

He holds a glass of red wine in his right hand, crosses his leg, and stares at the ceiling. He laughs. He asks himself a question, then answers himself: he draws each passage as if sculpting a block of marble. His movements are just as soft as his voice, they are restrained calm; then sarcasm, black humor that falls by surprise and composes everything, but only as a warning that nostalgia will come later.

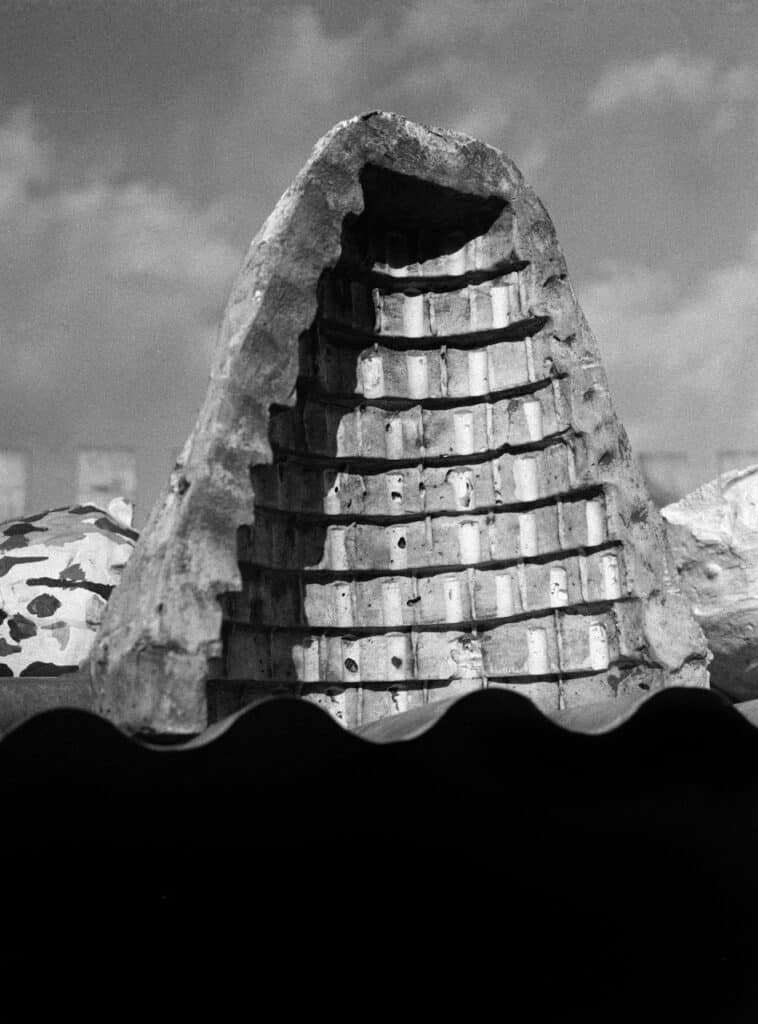

I get the sense that all the objects that are part of his house (the armchairs, the vases, a folding table, a bookcase, the glasses, the kitchen, the floor, a photo of his father, the framed drawings, the posters of Noguchi and Wolfgang Tillmans, Noah’s knives, the other photo of his father, the plants that adorn his window and even the fire escape on which we will end up sitting later, guessing the names of the skyscrapers) are covered by a very thin layer of whitish dust, like that which remains at the feet of the sculptor after giving form to what did not have in the first place.

Thus, then, Emile Kees gradually carves out his memory with words.

He grew up in Staple, east of Kent, in England, in a house that his parents built on what was once a farm. While the house was finished – my parents built it with their own hands – Emile and his sisters lived in a trailer sitting somewhere on that property Emile always calls the land. He stands up from his chair and, without leaving his glass, opens his computer to a real estate website to show me pictures of his house so I can better understand where he built his darkroom in the early days of the pandemic. Then, with that nostalgic irony, Emile tells me that the land is going on sale next week.

And the memory of Emile Kees occurs continuously in that four-acre property: it is his own succession of territories, the place where he became an artist, where he was fascinated by the perseids for the first time, and where the grass was always covered with marble detritus, a sign that his father, the sculptor Anthony Heywood, had begun to work outdoors, which for Emile inevitably meant the official beginning of summer.

Because art was always there: in addition to his father, his mother, Lily Heywood is a painter and photographer; his older sister, Nina Paloma, is a ceramist while his younger sister, Iona Lily, is a fashion designer: I don’t remember the first time I was aware of being surrounded by art, but I do remember the first time I wasn’t surrounded by it, it was as a child, at school, when I discovered that being an artist wasn’t something normal.

***

The death of his father in 2022 also meant the end of a cycle: it marked the end of two years of intense photographic production in the land and the beginning of his new life in New York. When Emile arrived last August to live in the East Village, he brought with him more than seven hundred negatives that he would develop and print over the following months.

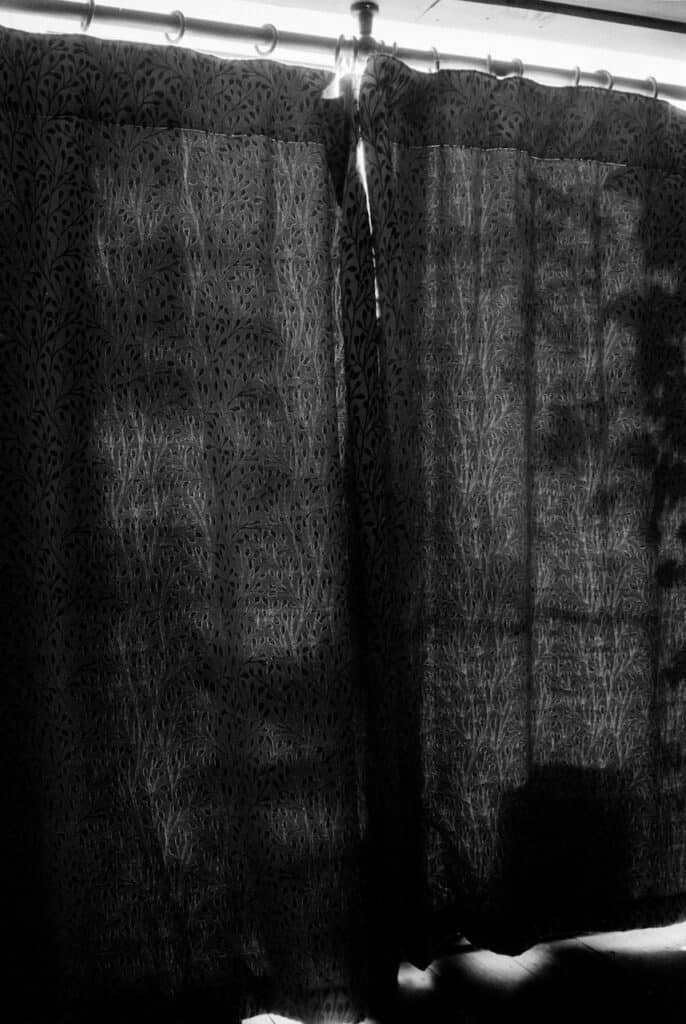

Last May, as part of the joint exhibition Lifelines at the International Center of Photography, Emile included three photographs from that corpus: a stone mold, a plant behind a translucent curtain, an eyeless horse; below them rested a white shelf displaying a black book within everyone’s reach, secured only by a safety cable.

Emile stands up from his chair and reaches out for a box resting on a shelf just above the doorframe leading to his bedroom. From it, he pulls out the book, Meteorites, a compendium of his personal diaries and a series of photographs taken since the beginning of the pandemic, up until his father’s death.

And as I flip through the book, examining the images and reading certain phrases in the texts, lists of things and moments, Emile looks up at the ceiling again, remembering the story for which the book is named Meteorites: that was an extraordinary coincidence, to see that meteorite next to my father. I’ll never forget his face, and it’s been sixteen years. He was impressed to see that meteorite pass above us straight into the horizon. And then another one. I was nine years old and I thought that happened all the time.

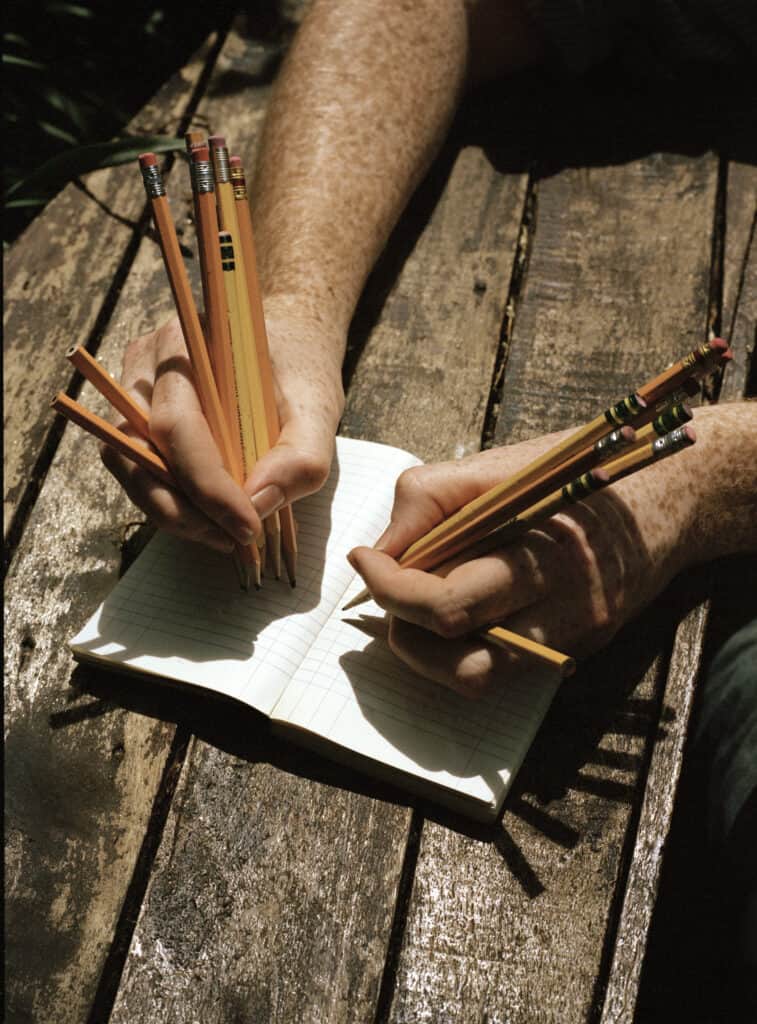

Emile seeks to make me understand the true textures, the colors with which he relates his memories or the metaphors with which he translates to himself different passages of his life, as if he had started to create the images long before he held his camera: a handful of transparent marbles falling on the table the day his father told the family he had cancer, the blue light of a meteorite, the yellow color of a hospital: my approach to photography may seem like an abstract statement, but I didn’t want to take pictures, I wanted to take pictures.

***

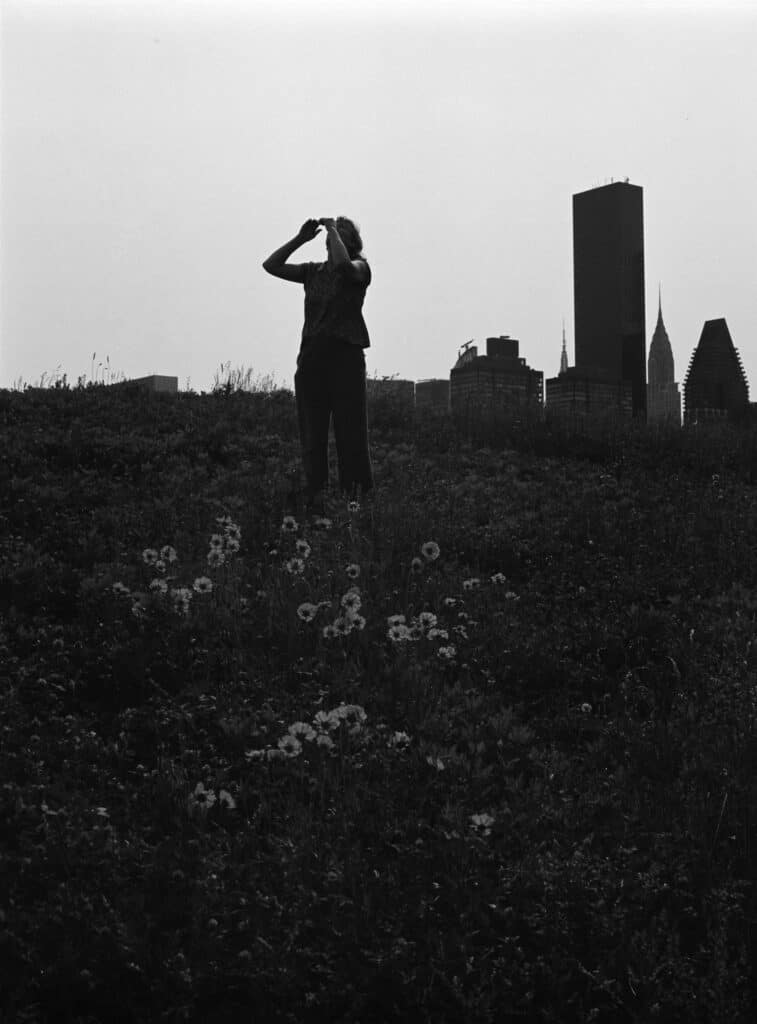

For a while now, the fire escape has served as our balcony. The humidity has already flooded New York and this narrow piece of wrought iron, embedded in the facade of its building, is our only escape. Emile is sitting on one of the steps and I am leaning against the railing. He takes a sip from his wine glass and tells me about the polytunnel in which his father had long kept more than a hundred marble and bronze sculptures and which, since his death, Emile has been in charge of emptying: Dad was always awake. Always working. Cleaning that place, I learned things I didn’t know about my father, suitcases from trips, photographs, letters.

New York, now, is a permanent conversation with him. Sometimes he likes to imagine being with him in certain, sometimes improbable places, like the Noguchi garden, especially, or one of the rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art next to a Brâncuși: it’s like riding by on a bus and seeing him from the window.

Until a few years ago, his work was amateur and spontaneous, it was the pandemic that brought the possibilities. But also the beginning of a very difficult time: my work may seem solid and stable, but I never see it and never will. Every week my approach to photography changes. The fact that I have built a darkroom, working with analog. My inspirations are constantly changing.

And at one point Emile stops, looks down the street, and says to me: my mother always tells me that everything influences everything, I grew up learning that. And if everything informs everything, as Emile believes, it is easier to understand his photographs as sculptures, a way to preserve, to give form to what has no form.

As I watch Emile contort himself back into his apartment, I think of his life happening at various times, at the same time: in an empty polytunnel, on a farm, on this service staircase where we are now, in Edinburgh, on a beach in Mexico, on Roosevelt Island, standing next to his mother and looking at the floor, in a darkroom: photography is like a perpetual horizon, a utopia.

For Emile, photography is never stopping, never reaching the end, never knowing anything. Never.

That’s what it’s all about. EP