Let’s start from the end:

We said goodbye outside the F subway, in Delancey, while some drunk people were arguing in front of the door of McDonalds. Five minutes ago, Carlos (or Andrés, as he has always been called) was talking to me about tenderness, about the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, holding the last sip of beer in his right hand and with his elbows resting on the table, shoulders raised, telling half lies that in the end are the truth, whole truths that are a bit of a lie.

But to be in this bar, which name in Spanish would be ridiculous, we had to walk to it, cross Delancey, cross Essex, and before all that, before a limousine threw a puddle at our feet, before lighting a cigarette that we would not finish, we had to discover that the storm was finally over, decide that we would leave that apartment on Broome Street where we had taken refuge, sitting, on the floor, talking about childhood, photography, anime and bad mezcales. We had to get up from the floor and I had to write in my notebook the last thing I would record of my conversation with Carlos that night: I don’t control anything, and Carlos had to say it with more pride than resignation, so that I would decide to uncap my pen, after having simply asked him why he always seemed to have everything under control.

And the fact is that, to understand Carlos, to even try to understand his work, you have to start at the end, you have to understand that in photography and in the darkroom, time does not exist or has no order or simply is not time, and that’s it.

Nothing else.

Carlos de la Sancha was born in Mexico City in 1985 and defines his practice as a curiosity, a benevolent foolishness to understand the limits of photography. A quiet storm, he says, laughing, but knowing that it is absolutely true that for him, photography is not fiber paper or negative, but search, memory, tenderness.

He doesn’t talk much about his childhood in Córdoba, although he does mention one detail, the fact that he and a group of friends had a common dream: to buy a 110 format camera and register each of the things they did, each of the experiences they invented, the afternoons after school. But in the end it remained just a wish, one of those memories whose veracity confuses the memory, but it is just that anecdote, the one about the camera he never bought, that Carlos uses to confirm something he had told me before: photography is a latent desire.

Carlos floats in three universes: the Bronx, Brooklyn and the Lower East Side. In the Bronx he teaches documentary photography to high school students; in Brooklyn, at Worthless Studios, he is a photographer and leader of the Free Film program; and at the International Center of Photography, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Carlos is a staff member and alumnus of the Creative Practices program.

Believing you know everything is the dumbest thing there is, he says, after talking about his time studying photography in Berlin and his time at the Escuela Activa de Fotografía, there are people who truly believe they know everything and that’s the start of everything that’s wrong. Then, after agreeing that we have all been there at some point, the conversation leads us to Roland Barthes’ winter garden and how, far from that canon, he prefers to look at the Greek myths and see from there his relationship with the camera and the chemical process in the darkroom: photography is not death, but desire.

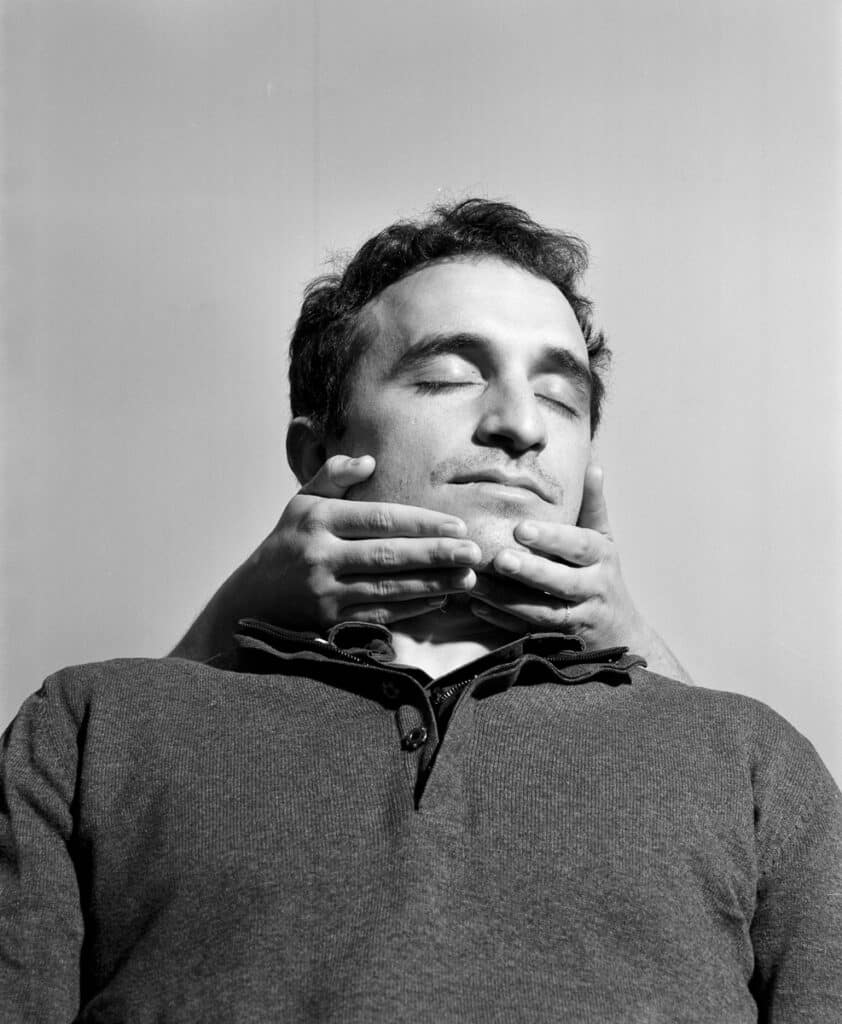

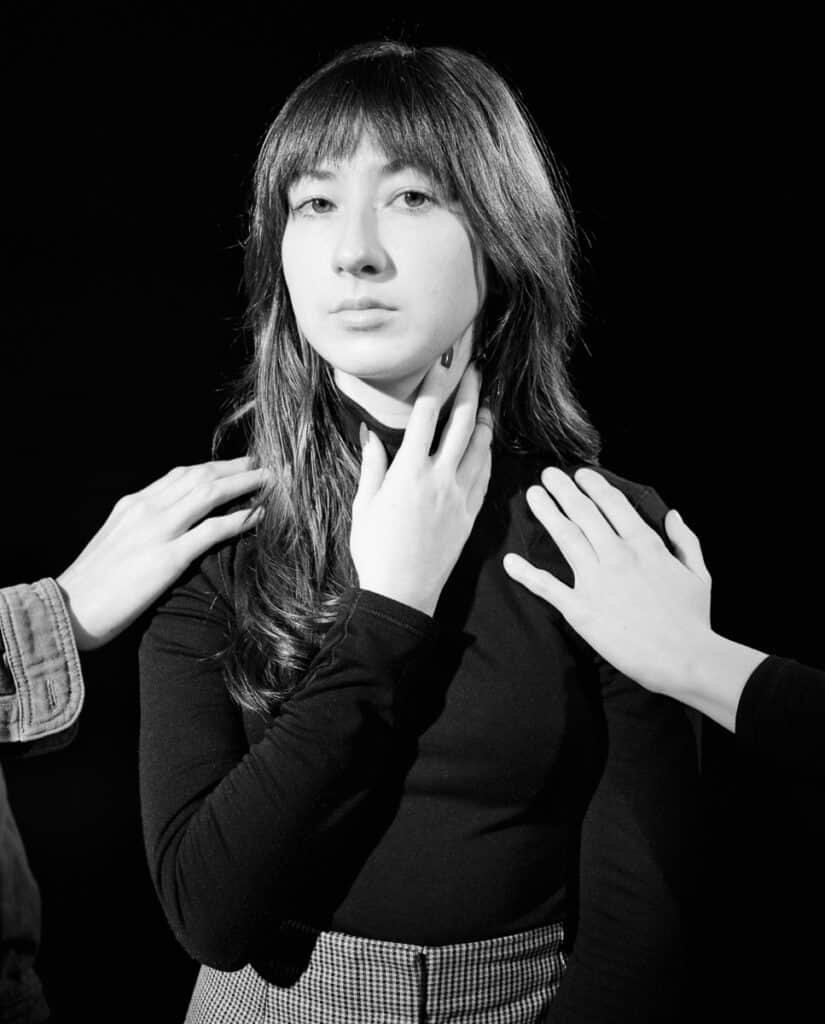

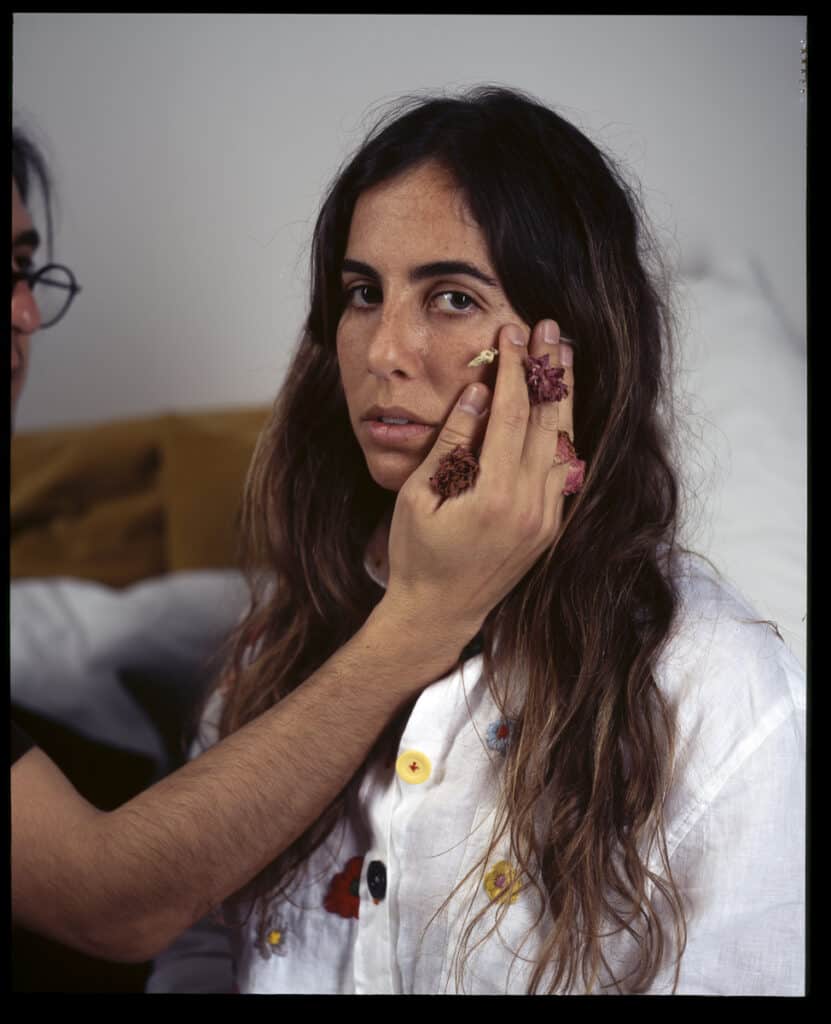

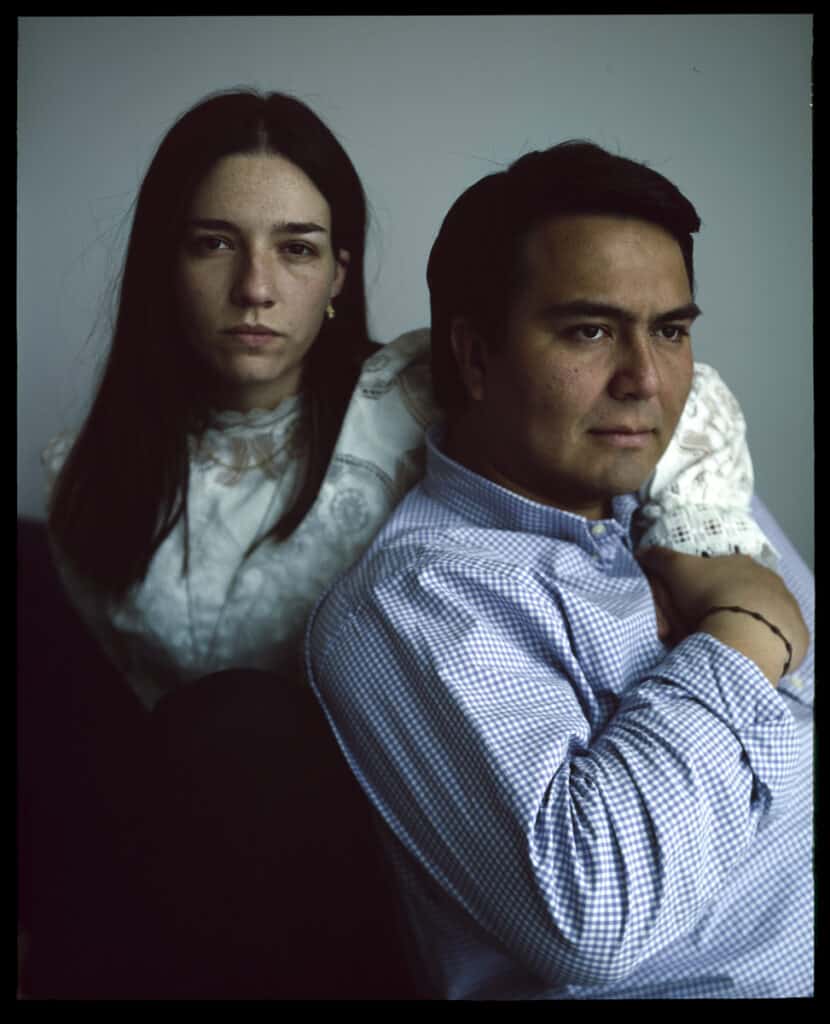

I don’t mind dying in oblivion, because for me, photography, what really matters about it, are the connections. And suddenly I am reminded of that time, earlier this year, when he took some large format portraits of María Prieto and me, in our apartment. Carlos was preparing the plates and the focus, María and I were watching through the window, in silence, waiting for the moment when Carlos would shoot.

Photography then became silence.

***

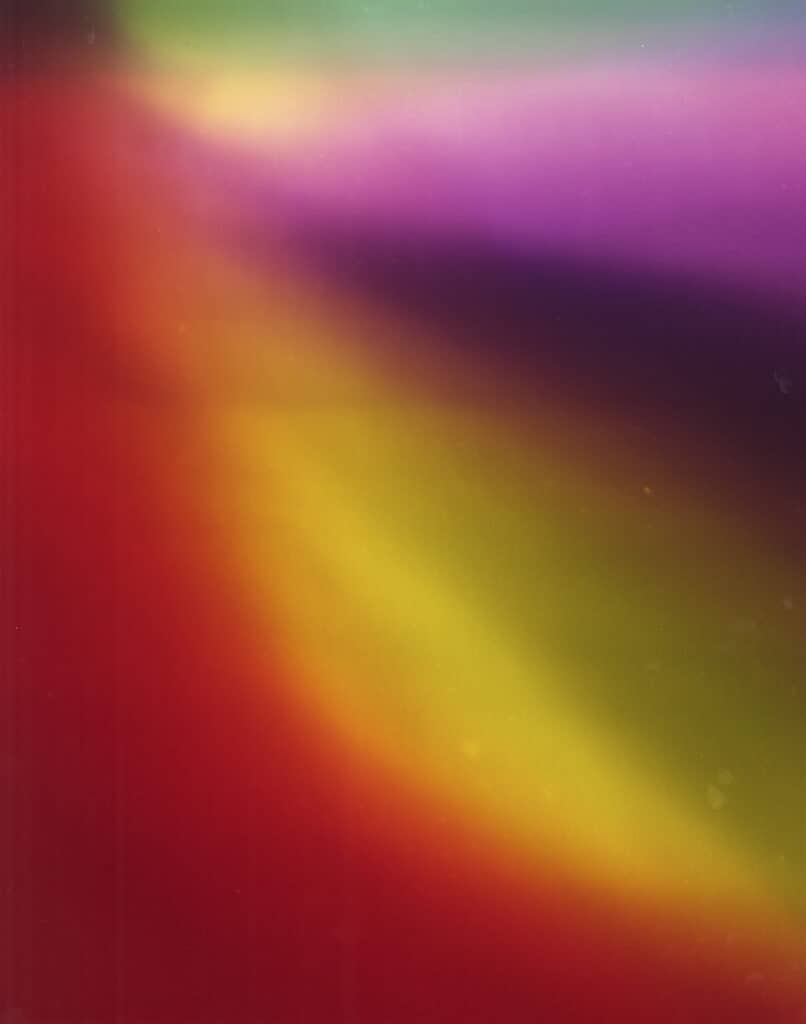

It is Sunday. It has just rained. In the Kunstraum gallery in downtown Brooklyn, several people are gathered around a peculiar work: a strip of three meters long and about fifteen centimeters wide that hangs from the wall, goes out of its limits and ends up on the floor. Some, distracted, are about to step on it, and when they are warned, they admire the work with more interest. Carlos de la Sancha talks about this work to a group of people: I am looking to push the boundaries of photography, although I do not believe in dualities, I move between them.

That color strip is part of a larger corpus that Carlos calls Vertical Horizons, a series of chromogenic prints that result from playing with light, filters and time inside a room in complete darkness.

***

Let’s go back to the beginning. The beginning of the beginning:

Nothing in the sky indicated ten minutes ago that the perfect sunset of the first evening of April would be clouded by a huge storm coming from the north, as if emerging from the antenna of the Empire State Building. Nothing indicated that we would have to rush up from the table where we were sitting.

To do so, we first had to choose the table where we would be for the rest of the afternoon, start our conversation talking about UFOs. Carlos had to take the metal chair and arrange it so that the sun would be in his face. Nothing indicated a storm, no wind, nor the totally black skies that would come later. And first of all, before starting as we started, Carlos had to answer the first question I asked him that afternoon, and to answer he didn’t even have to think about it: every day I ask myself this question. EP